Jessica Hetzel and Ava Xiao-Lin Rigelhaupt

At an event at the Jewish Community Center in Detroit on March 10, Ava Xiao-Lin Rigelhaupt, a writer, consultant, actress, speaker, and advocate for disability and autism representation, discussed her story and her work on the Broadway musical “How to Dance in Ohio.” The event, organized by The J’s Opening the Doors program, was in celebration of Jewish Disability Awareness, Acceptance, and Inclusion Month (JDAIM).

Ava identifies as a Chinese, transracial, Jewish, autistic adoptee. She shared her experiences of intersectional identities and how that affected her career in the entertainment industry. In Ava’s speech, she briefly touched on her experience of being diagnosed and how she managed it. Ava’s discussion of her multiple identities left the audience with a lasting impression of the importance of inclusion and belonging among various communities. [continue reading…]

This week, MacKenzie Scott’s Yield Giving announced RespectAbility as one of the Yield Giving Open Call’s awardees working with people and in places experiencing the greatest need in the United States.

This week, MacKenzie Scott’s Yield Giving announced RespectAbility as one of the Yield Giving Open Call’s awardees working with people and in places experiencing the greatest need in the United States.

Kevin Iannucci, a rising talent in Hollywood, is raising the bar and challenging old stereotypes with his passion for acting and dedication to inclusivity. The 29-year-old Raleigh native’s journey into the world of acting began at the young age of seven with his older sibling’s encouragement.

Kevin Iannucci, a rising talent in Hollywood, is raising the bar and challenging old stereotypes with his passion for acting and dedication to inclusivity. The 29-year-old Raleigh native’s journey into the world of acting began at the young age of seven with his older sibling’s encouragement.

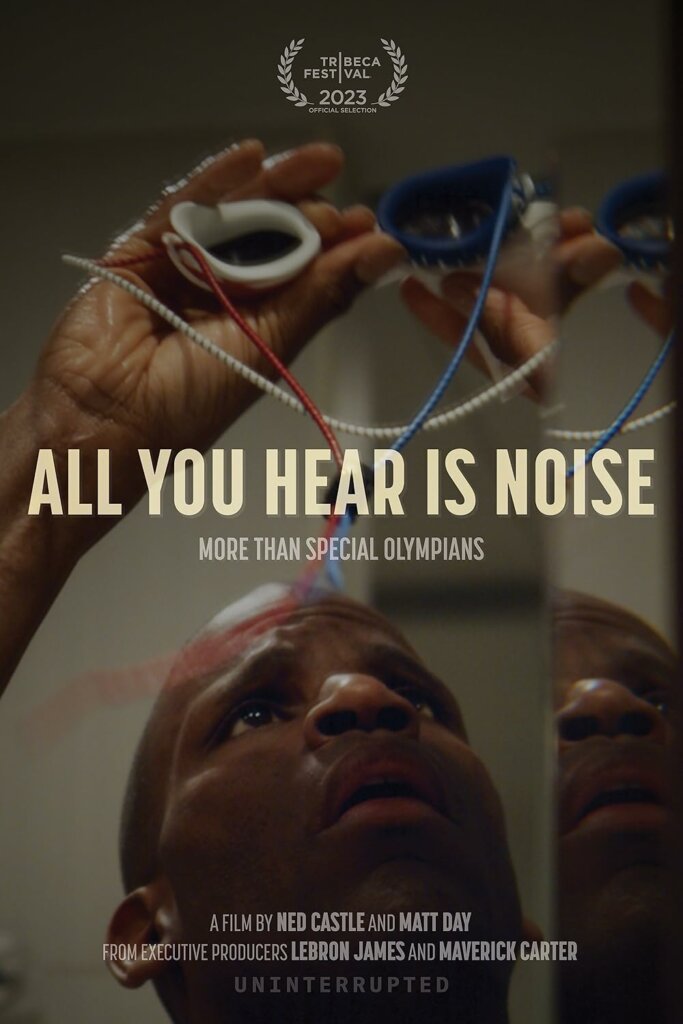

The documentary “All You Hear Is Noise” is a film of perseverance. Directed by Ned Castle and Matt Day, the film screened at the Santa Barbara Film Festival earlier this month after first premiering at Tribeca in 2023. “All You Hear Is Noise” follows the journey of three U.S triathletes – Trent Hampton, Melanie Holmes, and Chris Wines – training to compete in the Special Olympics World Games. Viewers gain a glimpse into their personal lives as they train to achieve a goal few achieve.

The documentary “All You Hear Is Noise” is a film of perseverance. Directed by Ned Castle and Matt Day, the film screened at the Santa Barbara Film Festival earlier this month after first premiering at Tribeca in 2023. “All You Hear Is Noise” follows the journey of three U.S triathletes – Trent Hampton, Melanie Holmes, and Chris Wines – training to compete in the Special Olympics World Games. Viewers gain a glimpse into their personal lives as they train to achieve a goal few achieve.