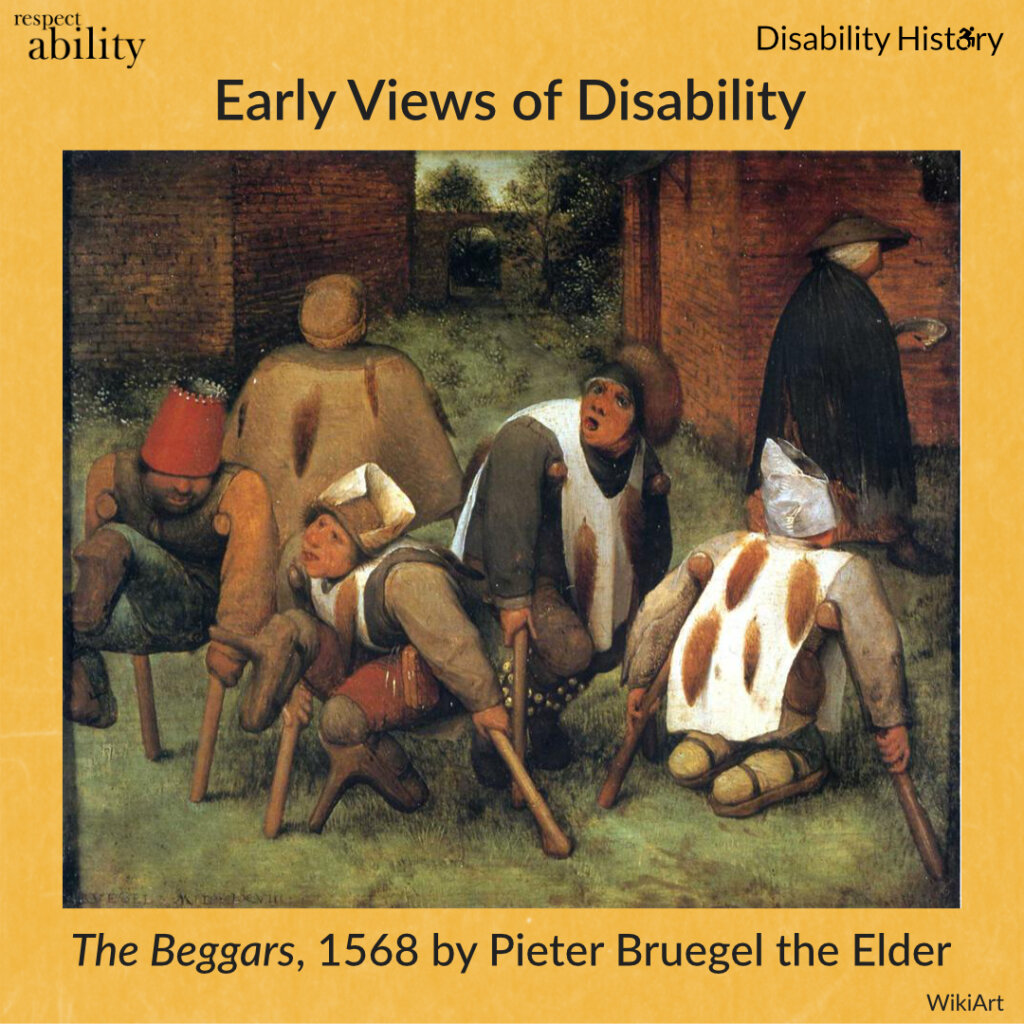

Leading up to International Day of Persons with Disabilities 2022, RespectAbility rolled out our Disability History series on social media. We hope the photos used in this series will serve as a reminder of the progress we’ve made, and motivation for the work that remains.

|

From the Middle Ages through the 1700s, people believed that disability was caused by a curse or sins. In Ancient Greece, Aristotle believed disabled people with unworthy of life and Plato was the father of the Eugenics movement, believing disabled people were broken. |

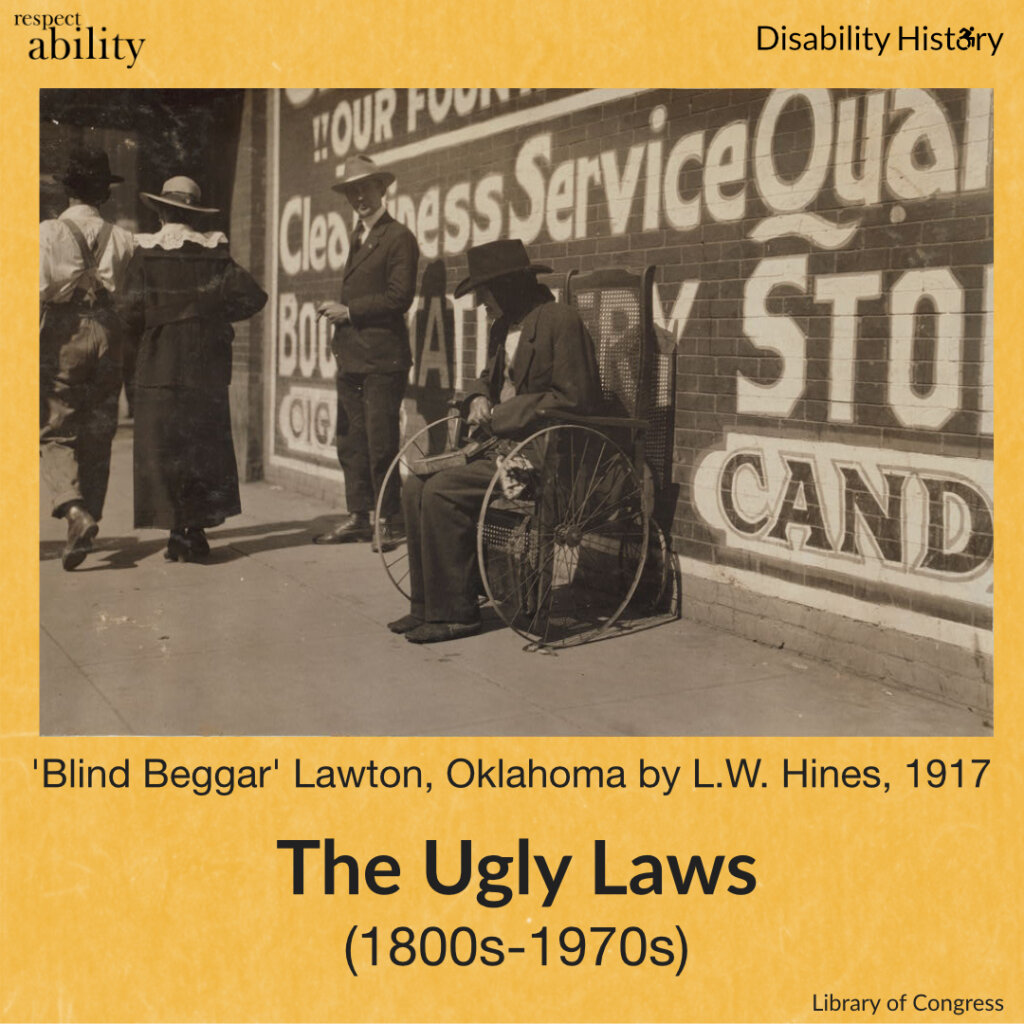

| In the 19th and 20th centuries, Ugly Laws throughout the United States made it illegal for anyone with visible disabilities to be in public view, as they were deemed ‘unsightly.’ Forced sterilization laws were also enacted across the United States. |  |

|

Carrie Buck was deemed “feeble minded” and “promiscuous” after being raped and having a child. The institution she was placed in wanted to sterilize her. In 1927, the Supreme Court ruled state forced sterilization of people with mental disabilities did not violate due process under the 14th Amendment. Buck v. Bell is looked back on as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions. |

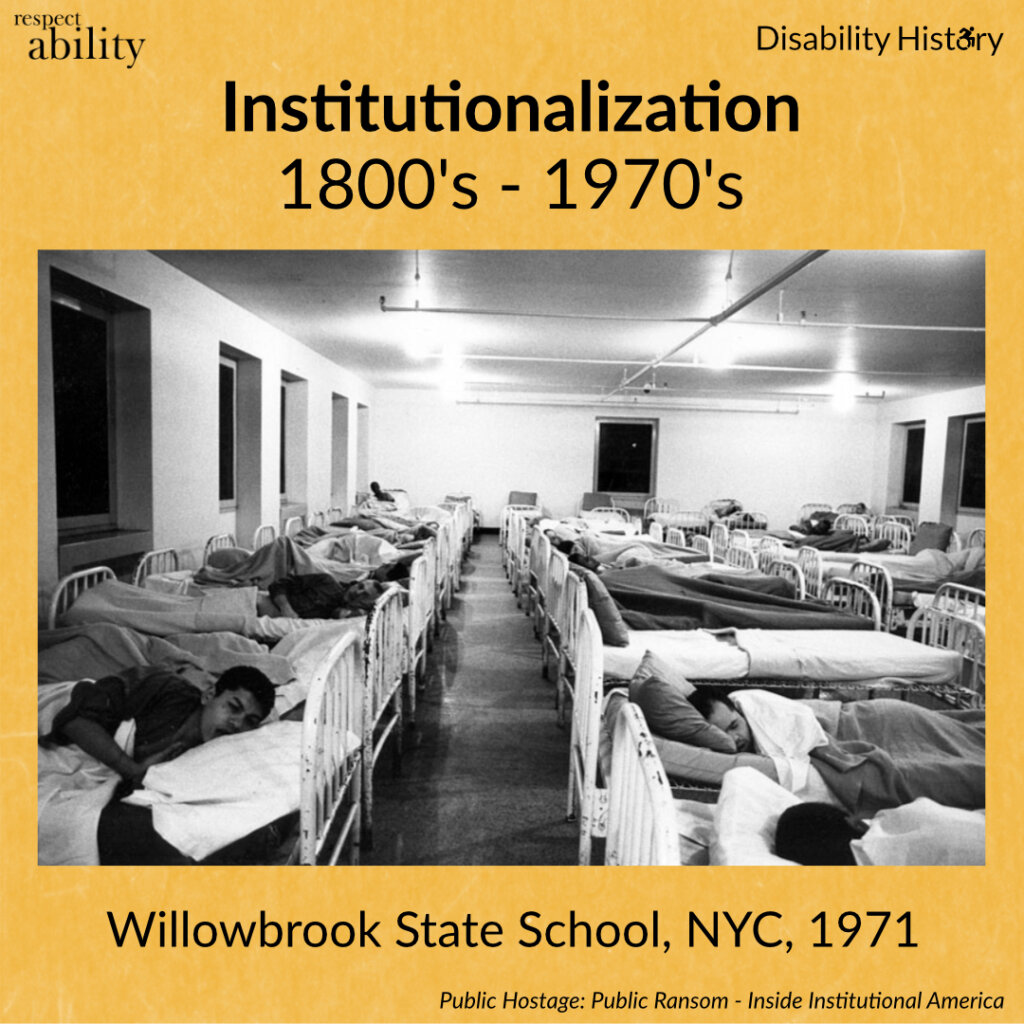

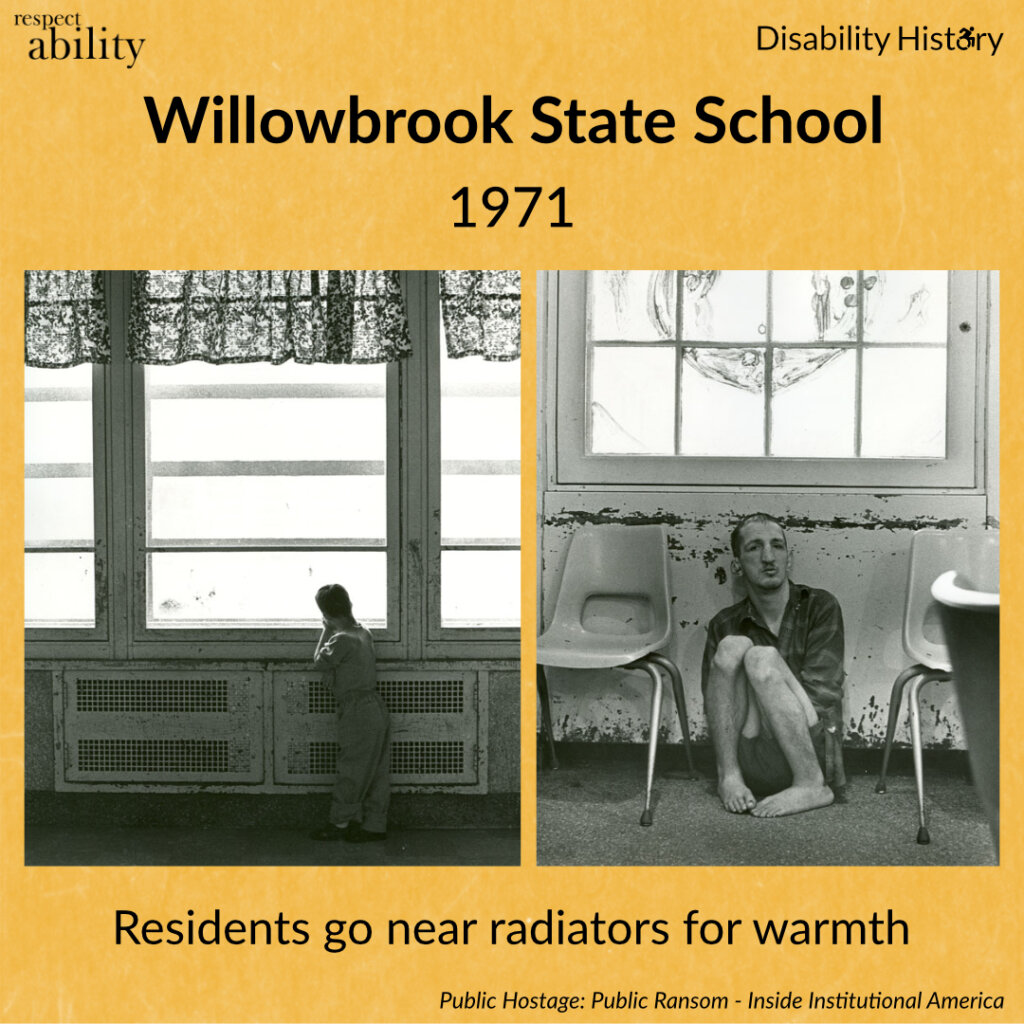

| Institutions opened in the 1800s and waned in the 1970s. Institutions held people with developmental, physical, psychiatric, and cognitive disabilities. The conditions were terrible and many people suffered abuse. |  |

|

One of these institutions was Willowbrook in New York. In 1972, Dr. Mike Wilkins and Dr. William Bronston helped expose the conditions at Willowbrook to the media, which led to public outcry and contributed to deinstitutionalization over time. Willowbrook was forced to make drastic changes after being sued by parents in 1972, but did not close until 1987. Learn more about the Willowbrook scandal in The New York Times. |

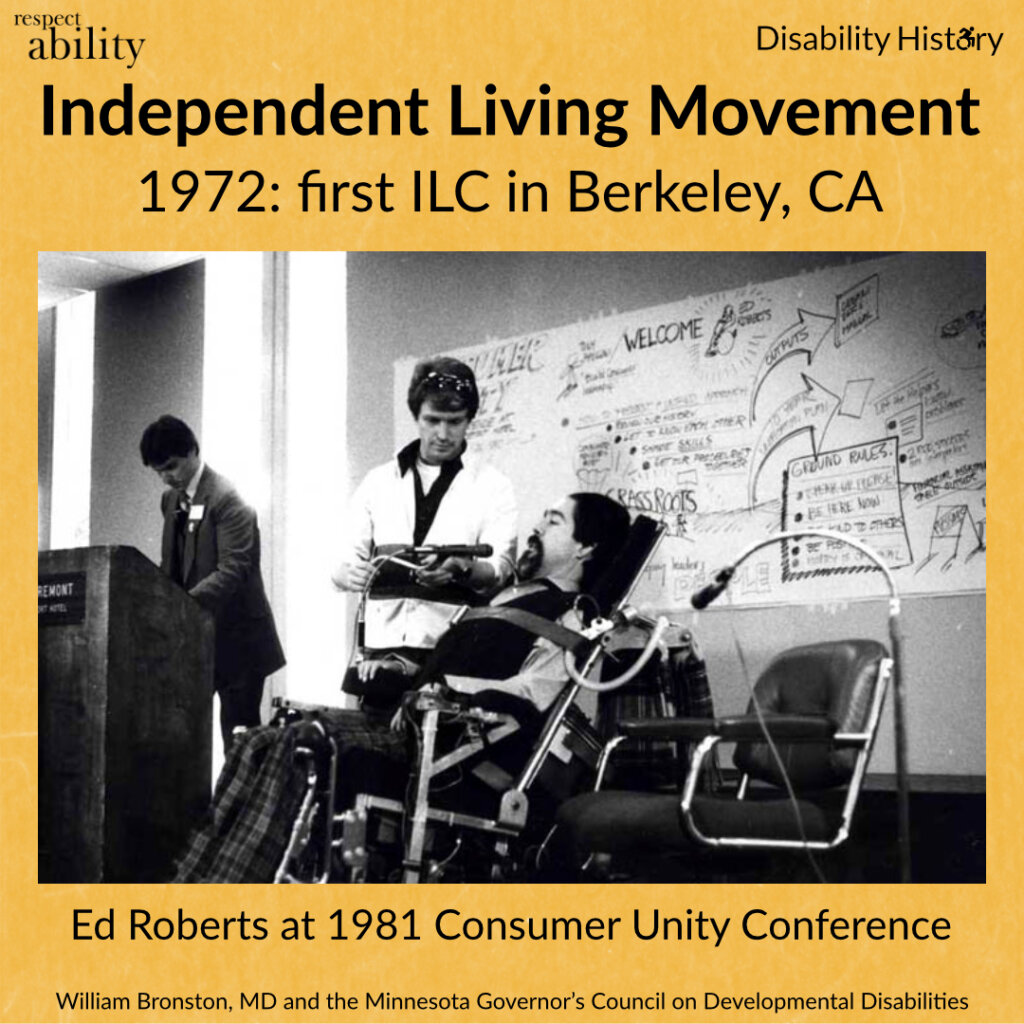

| People with disabilities were leaving institutions, but lacked rights and access to the community. The Independent Living Movement started when Ed Roberts, a disabled activist, fought to attend UC Berkeley, using part of the campus hospital as a dorm for students with severe disabilities. In 1972, Ed and the ‘rolling quads’ started the first Independent Living Center in Berkeley, CA to assist people with disabilities like himself to live in the community with needed services instead of hospitals. As a result, Berkeley became one of the centers of the disability rights movement. |  |

|

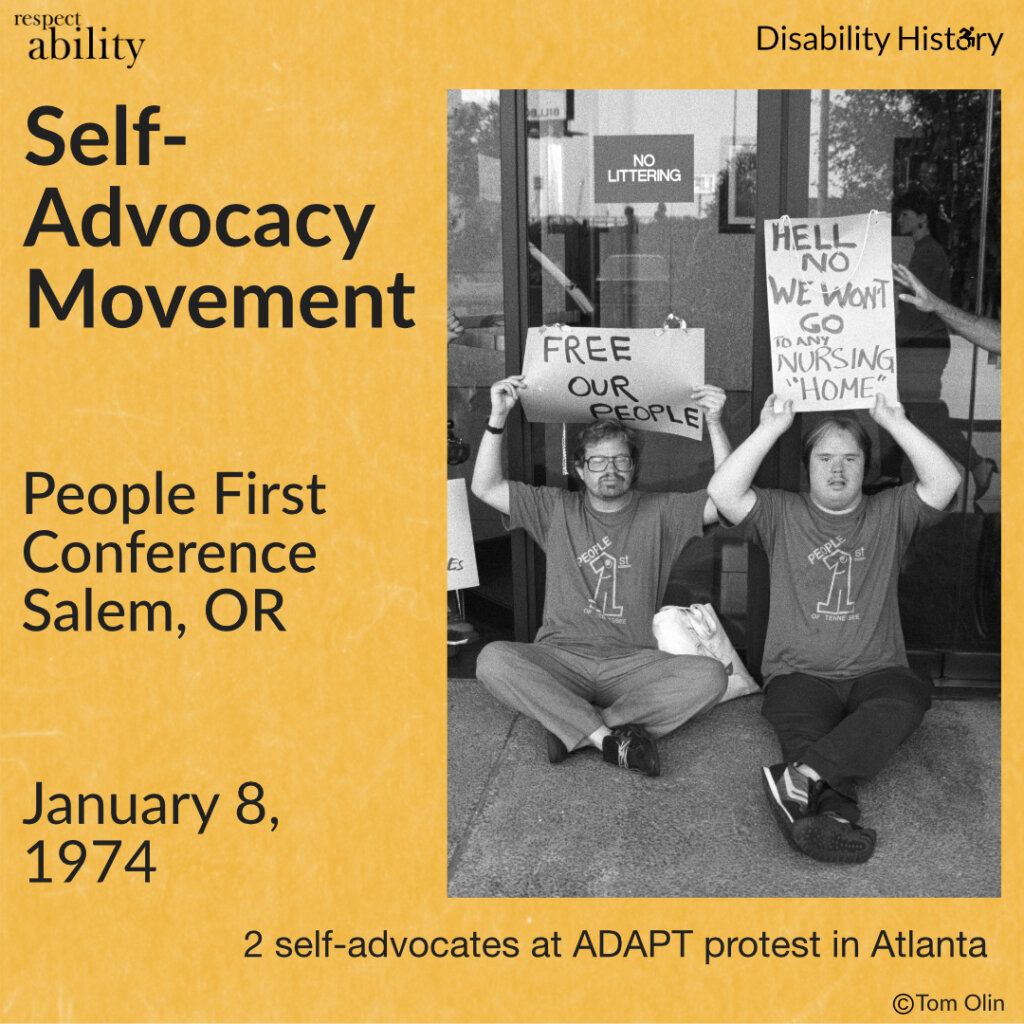

The disability-led advocacy movement began in Europe in the 1960s when people with intellectual and developmental disabilities started their own social clubs and discussed their desire for self-determination. This movement spread to the U.S. in Oregon when People First was formed and held its first conference in 1974. This advocacy movement fights for the rights of people with disabilities to make their own decisions and be recognized and treated as adults. |

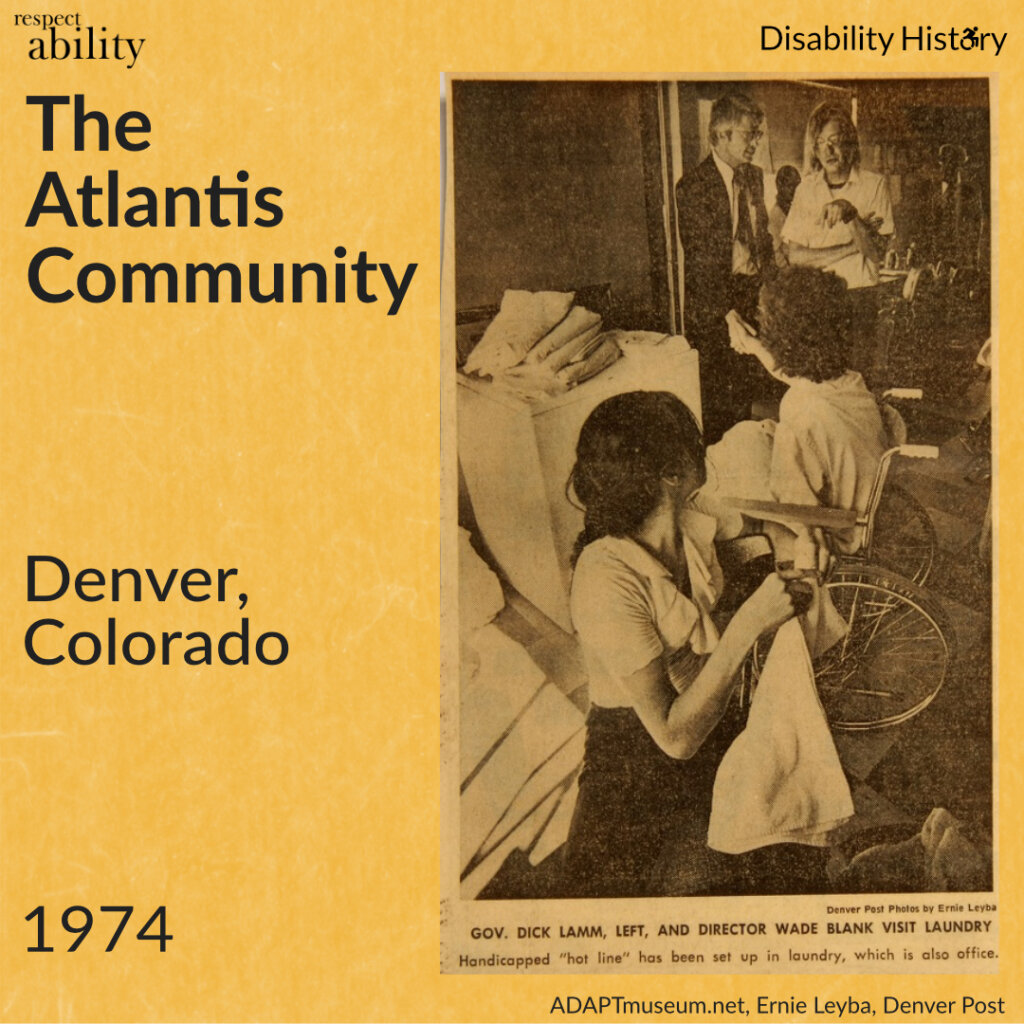

| In 1974, Reverend Wade Blank helped people with disabilities leave an abusive nursing home, typical of the time, and form their own community, the Atlantis Community, in Denver, Colorado. Before he came to Denver, he was involved in the Civil Rights and anti-war movements. After working at a nursing home, he helped people with disabilities fight for their rights. |  |

|

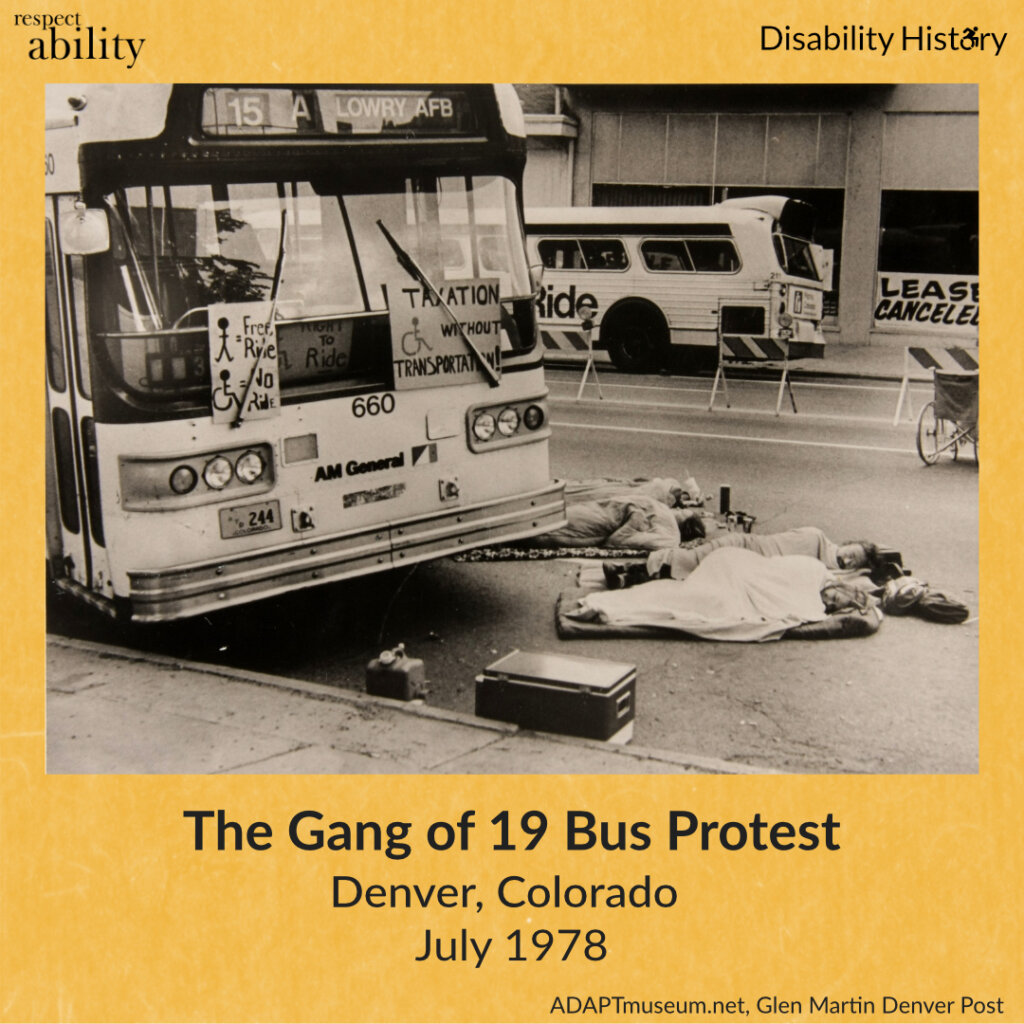

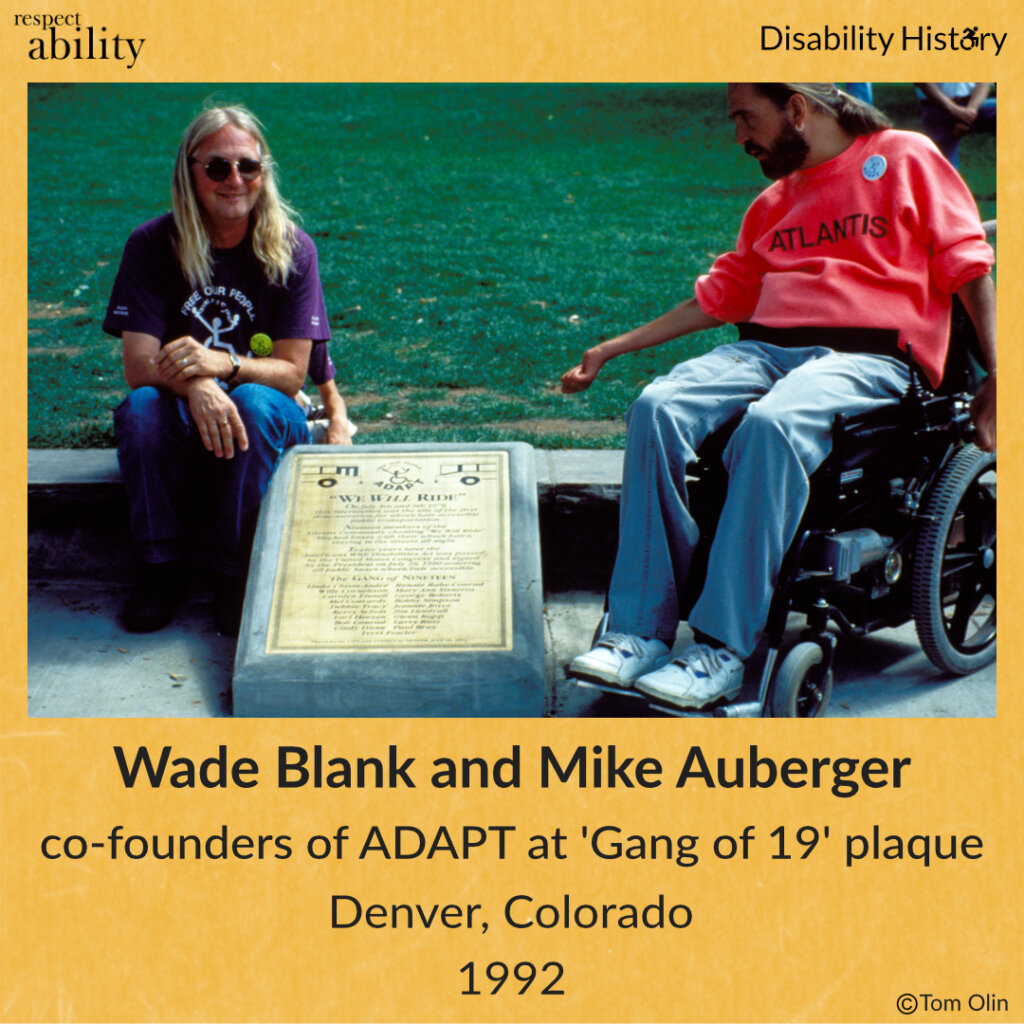

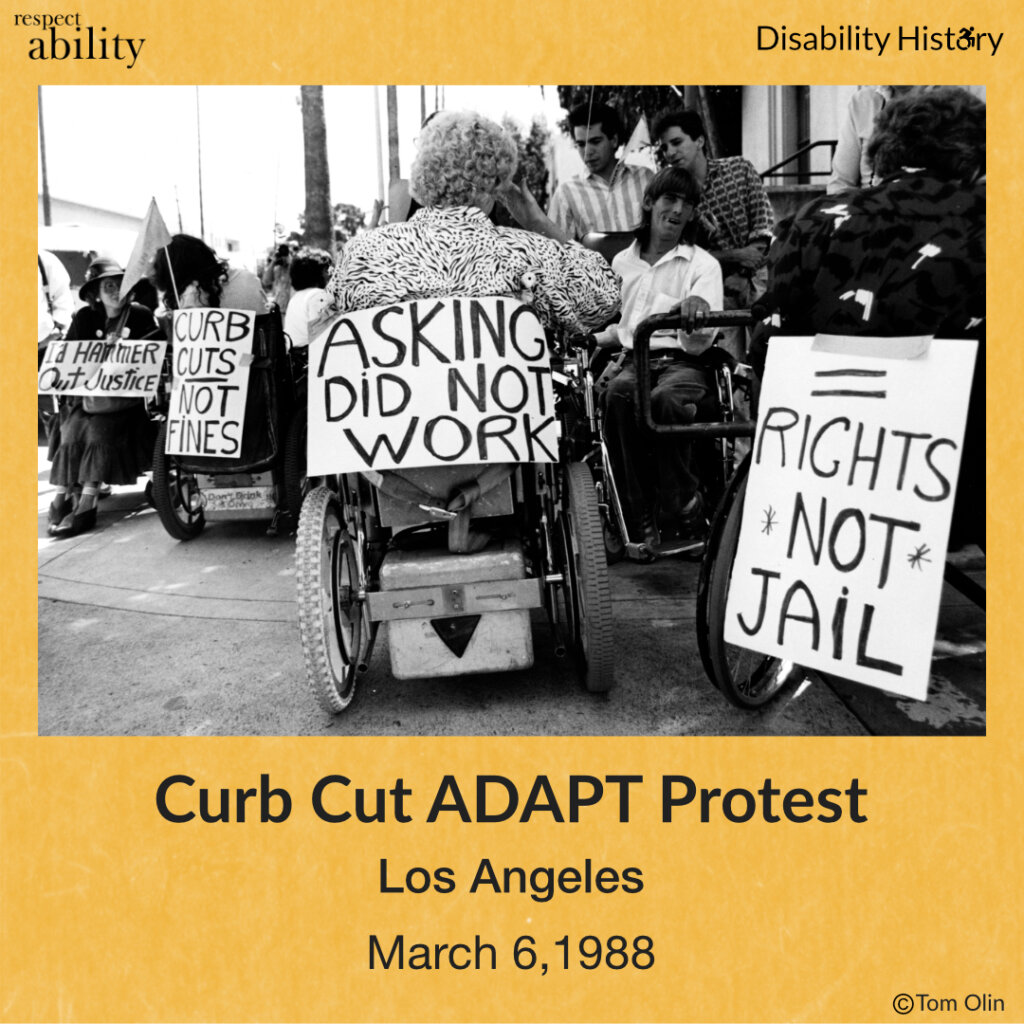

In 1978, 19 members of Atlantis blocked traffic in protest of the inaccessibility of RTD public buses inspired by the civil disobedience of the Civil Rights Movement. The bus protests continued and in 1983, Blank and Mike Auberger founded ADAPT, American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit. |

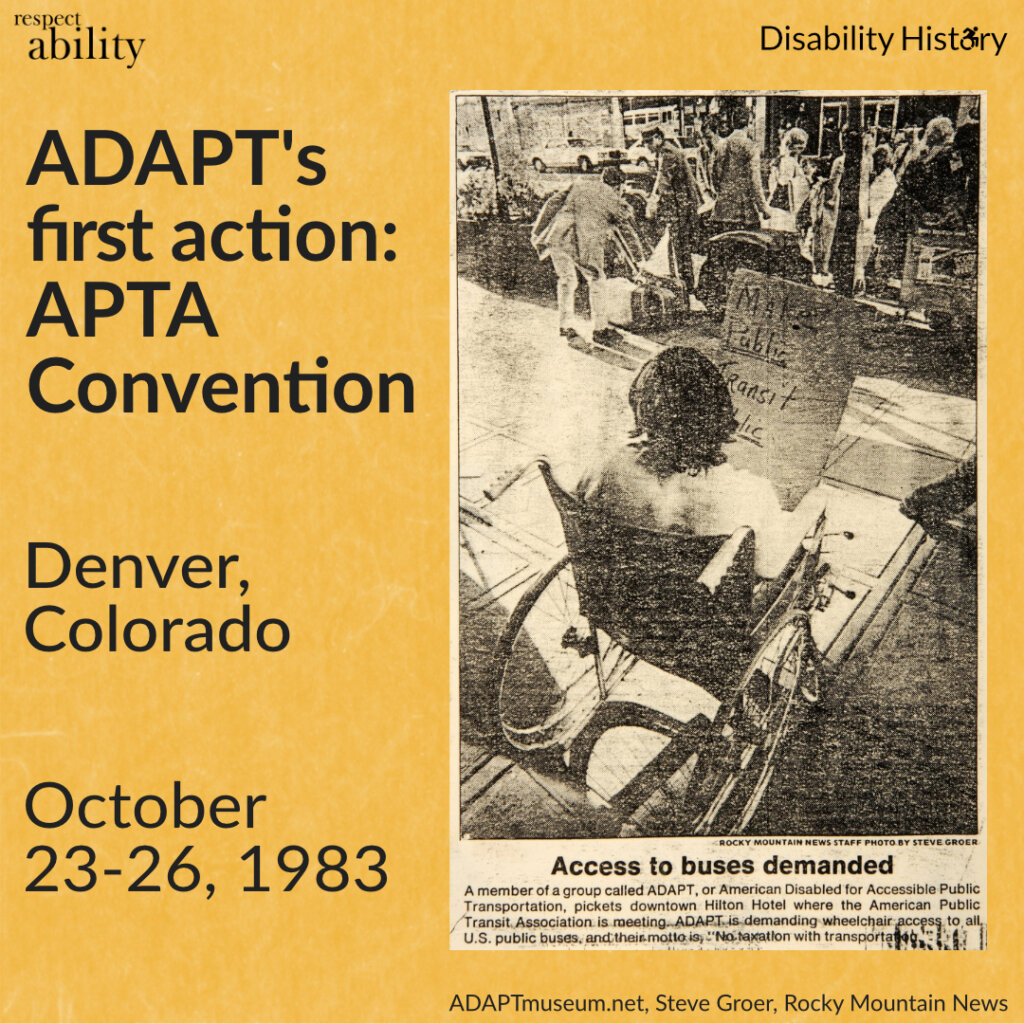

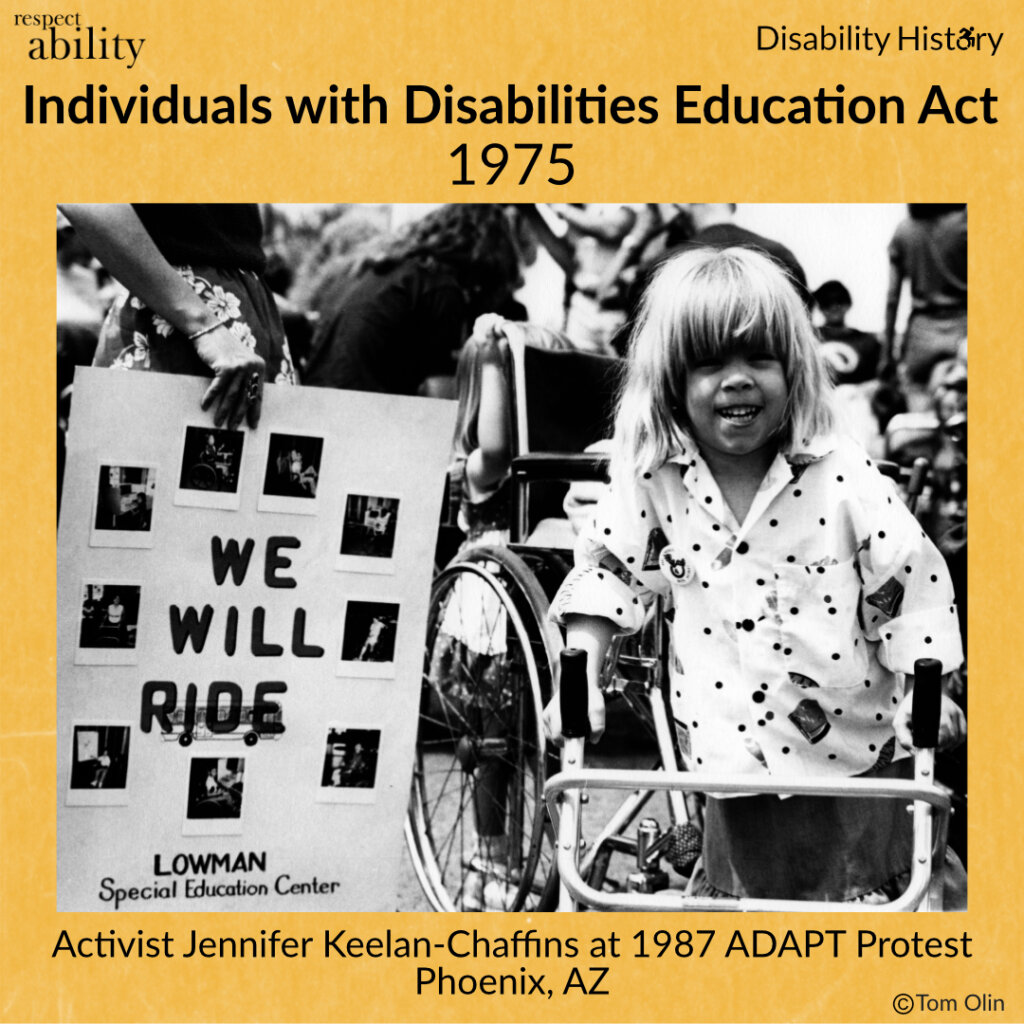

| ADAPT’s first protest was at the 1983 APTA convention. The work of the “Gang of 19” and ADAPT led to accessible buses in Denver and their movement spread across the country. |  |

|

ADAPT later became American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today and continues to fight for disability rights using nonviolent direct action across the U.S. Learn more about ADAPT at their website. Additionally, learn more about the history of ADAPT at the ADAPT Online Museum. |

| In Pennsylvania, parents sued when their children were not getting access to an education because they were disabled. In PARC v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (1972), the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania ruled that the state could not deny equal education because of disability, referencing Brown v. Board of Education. This led to the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, which was reauthorized in 1990 as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The law states that every child with a disability has the right to receive a free and appropriate education in the least restrictive environment appropriate to their needs. PARC is now known as The Arc of Pennsylvania. Learn more about IDEA at the official website. |  |

|

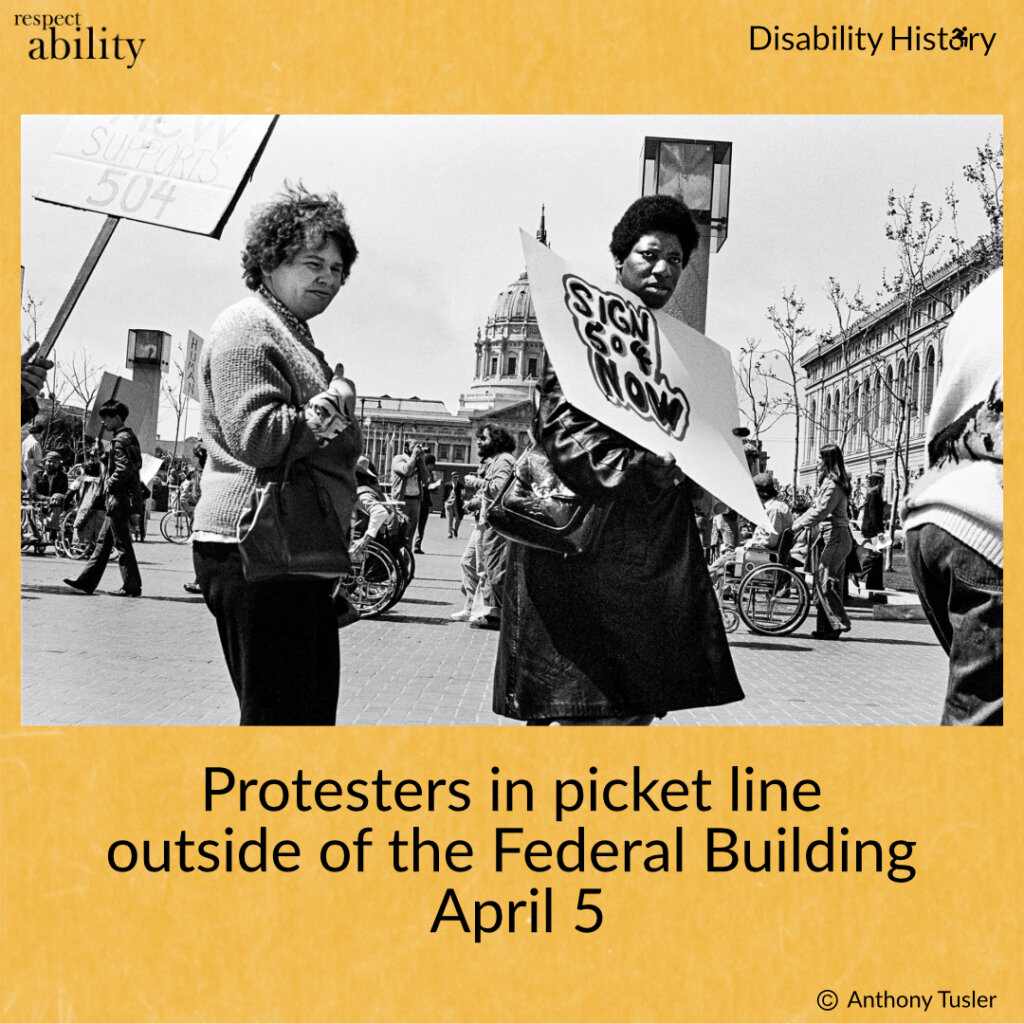

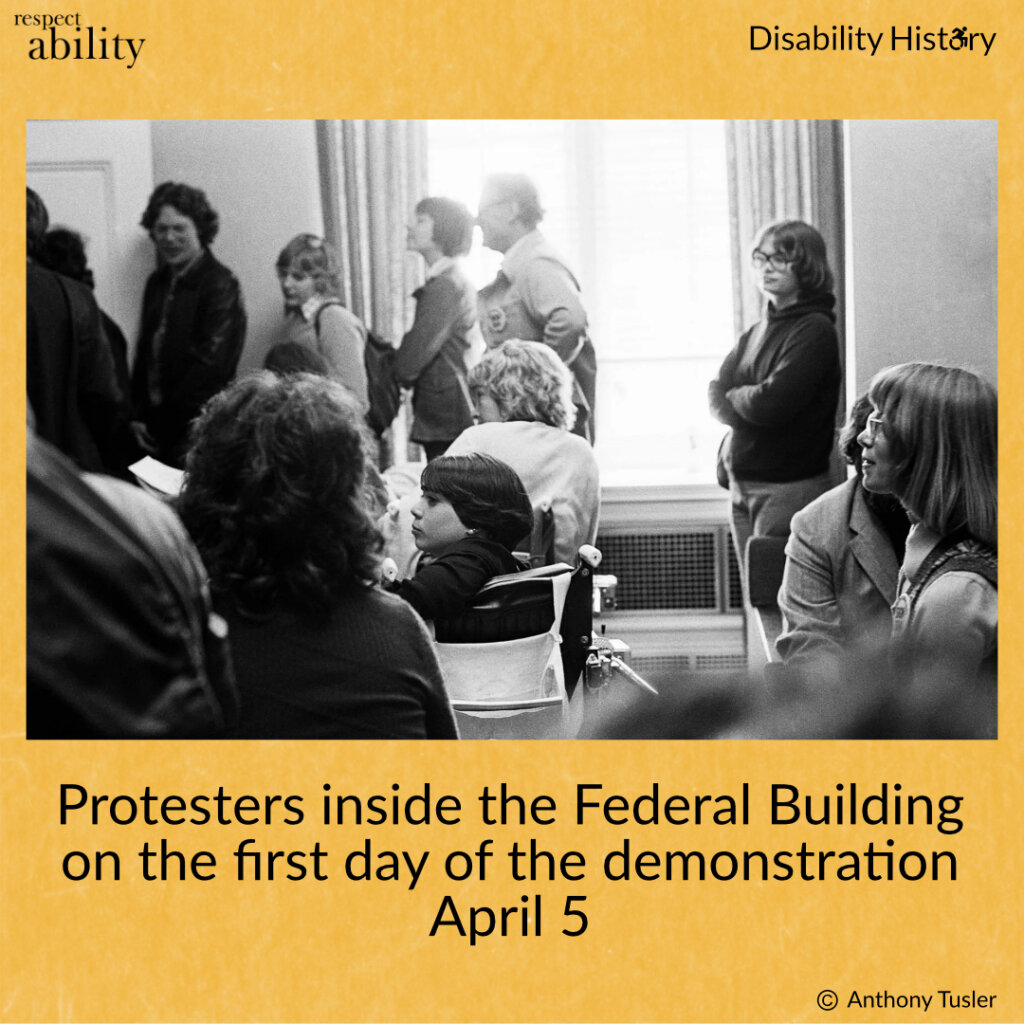

The 504 Sit In was the longest sit-in of a government building in U.S history, lasting 25 days. Learn more about this event at DREDF’s website. |

| After HEW (now HHS) Director Joseph Califano Jr. refused to sign the 504 regulations of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which protected disabled people from discrimination by the government and anything funded by the government, disabled people protested at offices around the country. The only one that lasted was in San Fransisco. |  |

|

The activists received assistance from labor unions, the black panthers and religious communities. The protest received significant coverage and a group of protesters representing the diversity of the group, including Judy Heumann, Kitty Cone, Dennis Billups, and Brad Lomax, went to D.C to further the cause and eventually meet with Califano, who would sign the regulations into law after their hard-fought efforts. |

| The 504 sin-in brought together many people with different disabilities and of all races, but inequities and prejudices still existed. Despite being a spokesperson for the sit-in, Dennis Billups was left out of important meetings and, along with other leaders of color of the event, is just recently starting to be recognized. He acted as “chief morale officer” during the sit-in and led the candlelit vigil outside the HEW director’s home that helped pressure him to act. Brad Lomax was a Black Panther active in both civil rights and disability rights. He helped start and run the East Oakland CIL sponsored by the Black Panthers. He also was an important leader in the sit-in and, along with fellow Black Panthers, was integral in the success of the sit-in. The Black Panthers participated in the protest, provided meals to protesters, and covered the event in their newspaper. |  |

|

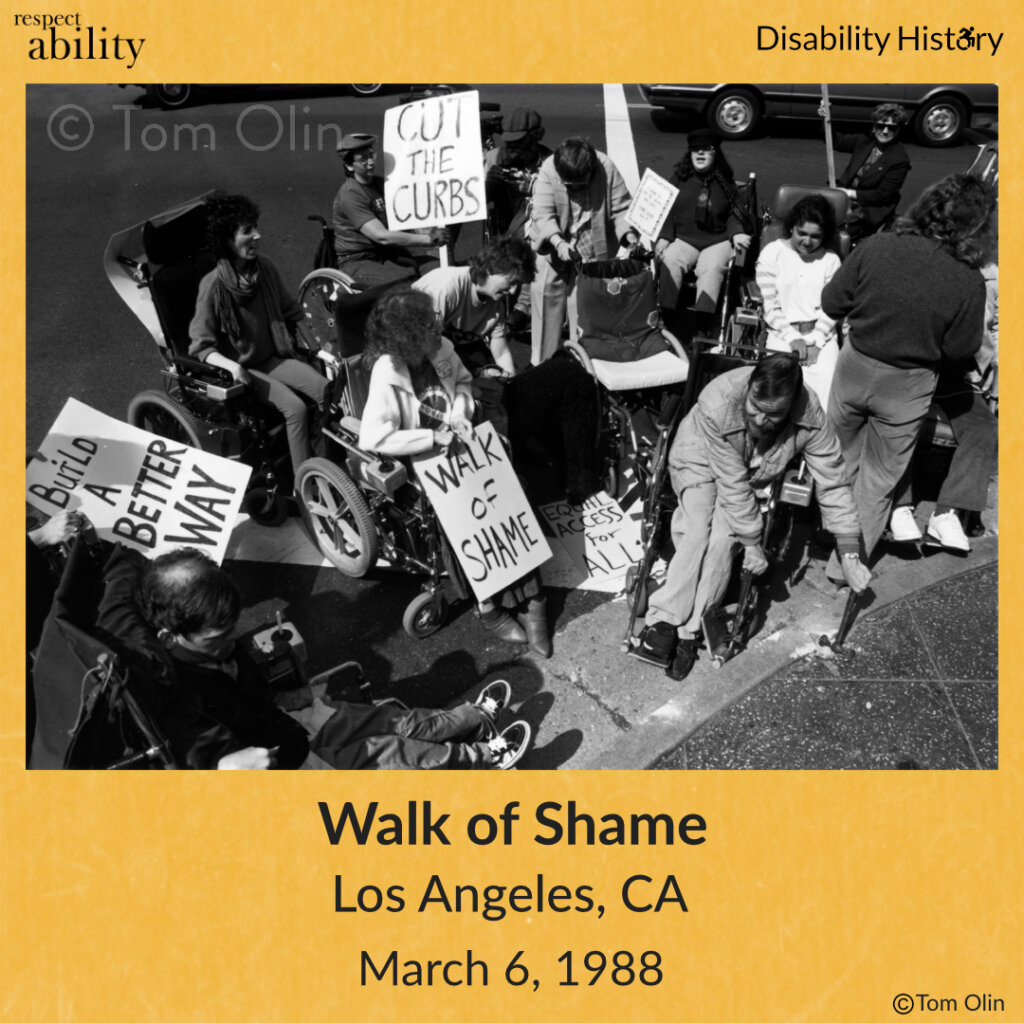

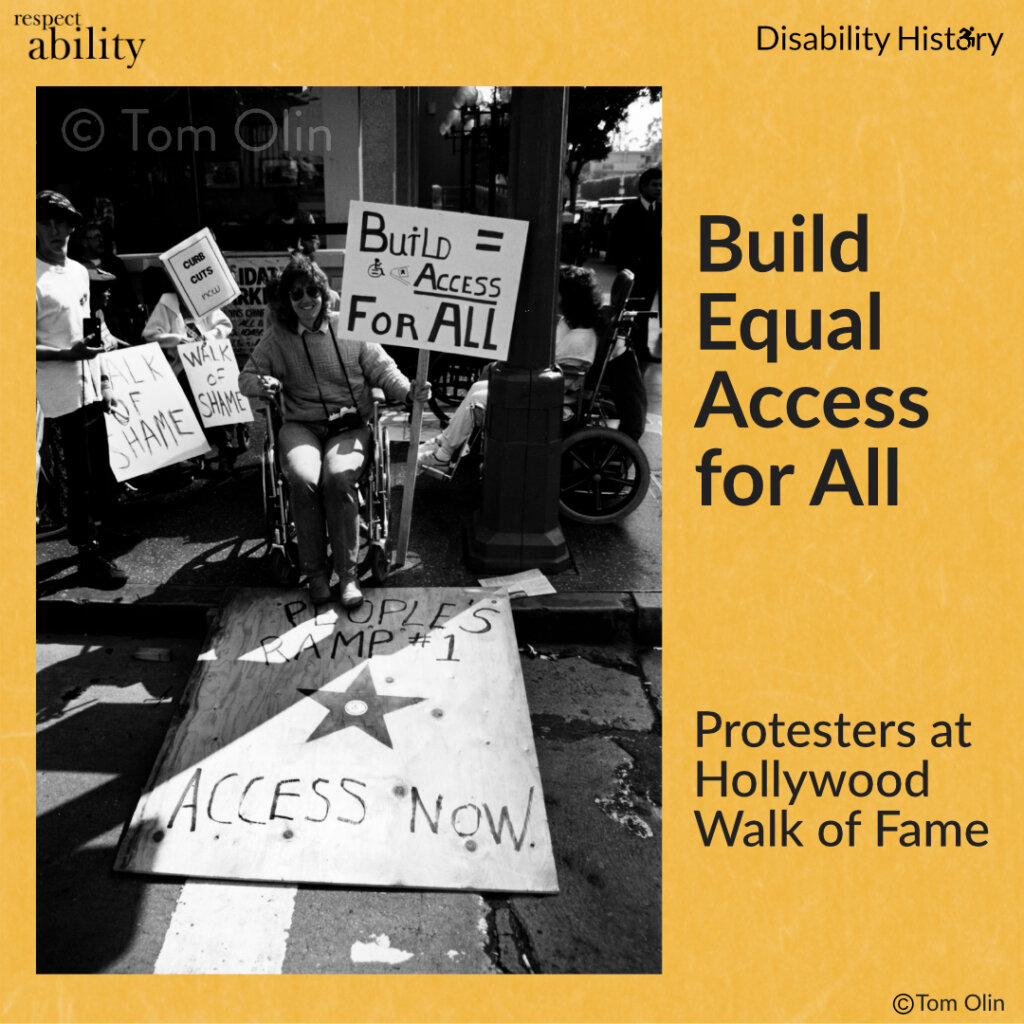

In 1988, ADAPT protesters took sledgehammers to the inaccessible “Walk of Fame” in Hollywood, chanting, “Walk of shame!” |

| Activists had been asking for curb cuts and accessible paths for years, but nothing was done and a wheelchair user was hit and killed because he was forced to ride in the street. |  |

|

The protest brought media attention. A congressman went to the protest and promised to make the sidewalks accessible in two weeks. |

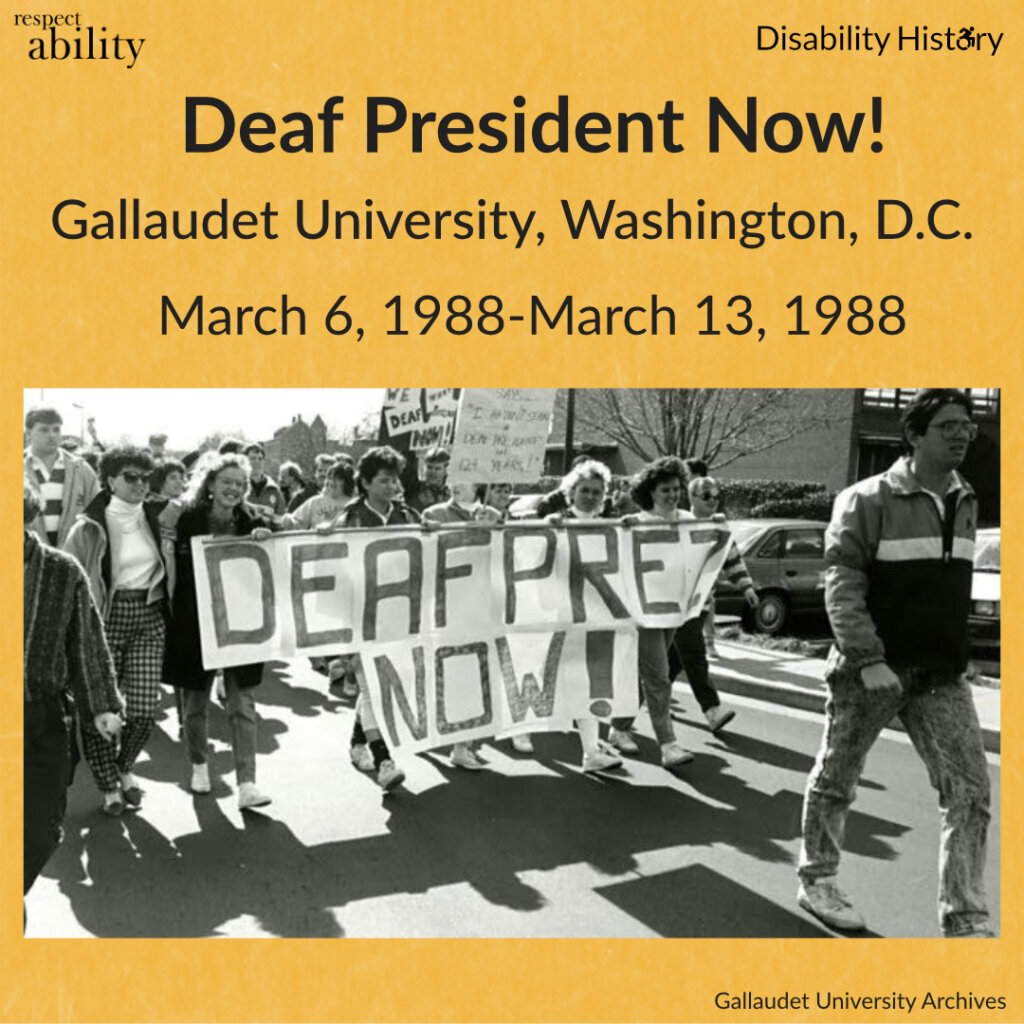

| Founded in 1864, Gallaudet University was the first university for Deaf and hard of hearing students. In 1987, the college encouraged Deaf applicants to apply when they were searching for a new president. Two of the three finalists were deaf, but Gallaudet announced they would be going with the hearing applicant. Students shut down the college in protest and gained support from around the world. In response to the activists’ demands, Gallaudet appointed Dr. I. King Jordan as Gallaudet’s first deaf president and agreed to create a Deaf majority on the Board of Trustees. Learn more about Gallaudet University at their website. |  |

|

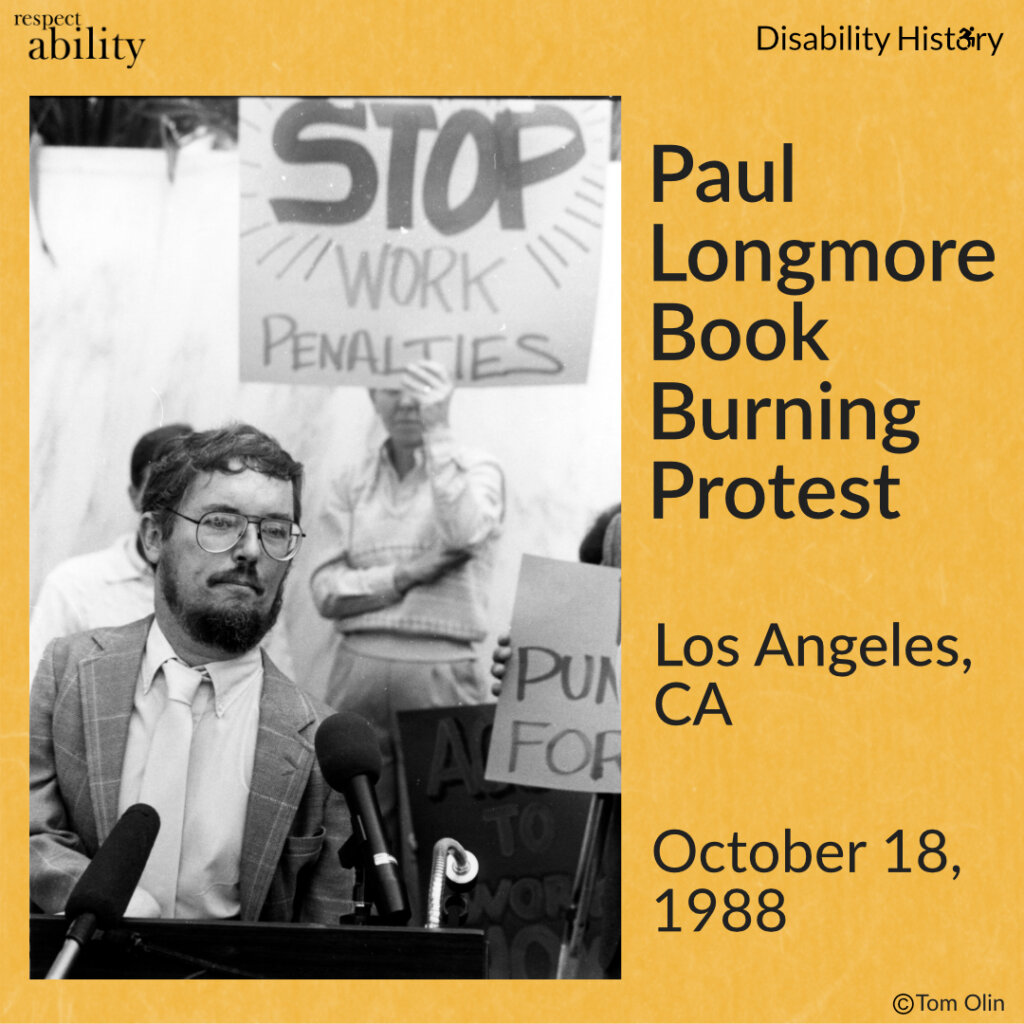

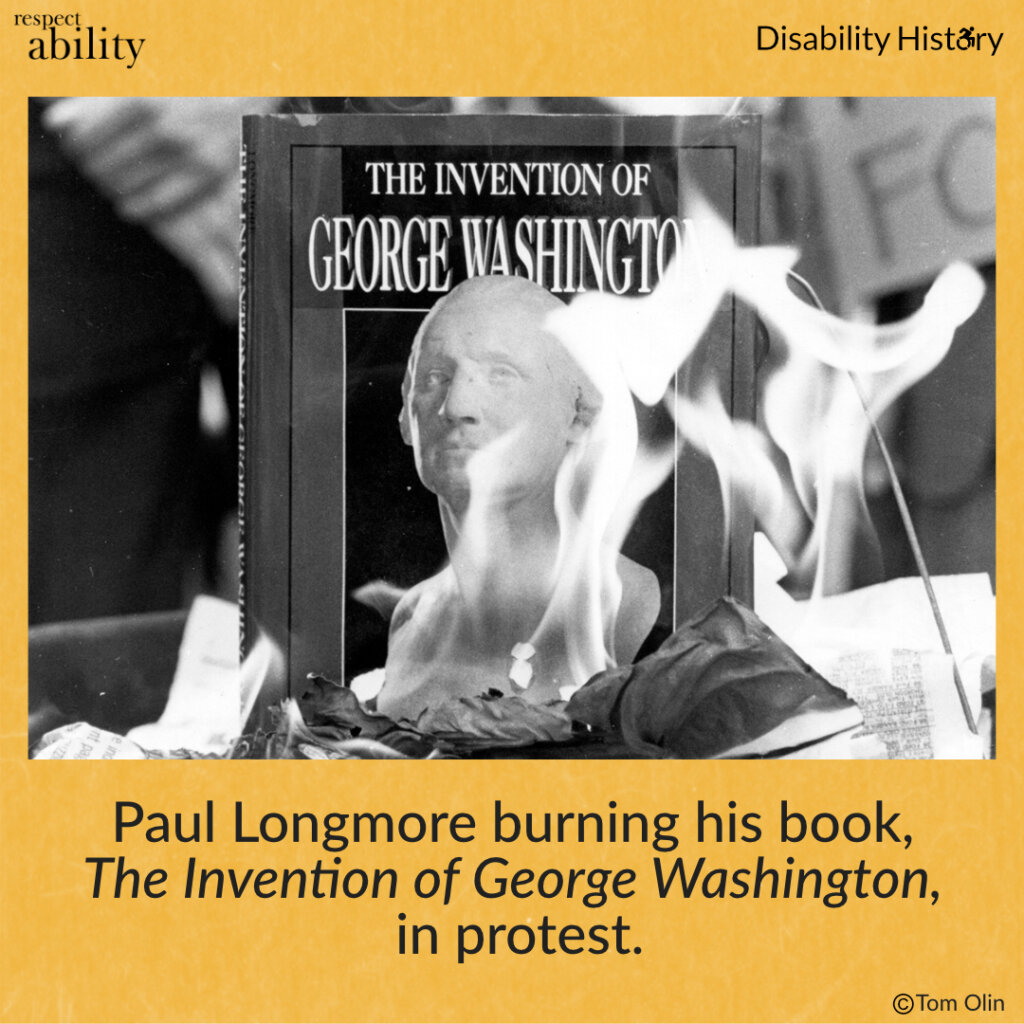

Paul Longmore was a disabled historian, author, activist and professor at San Francisco State University (SFSU). When he started earning royalties from one of his history books, he was informed he would lose his government benefits, including the in-home services he needed to live, as the royalties counted as unearned income. |

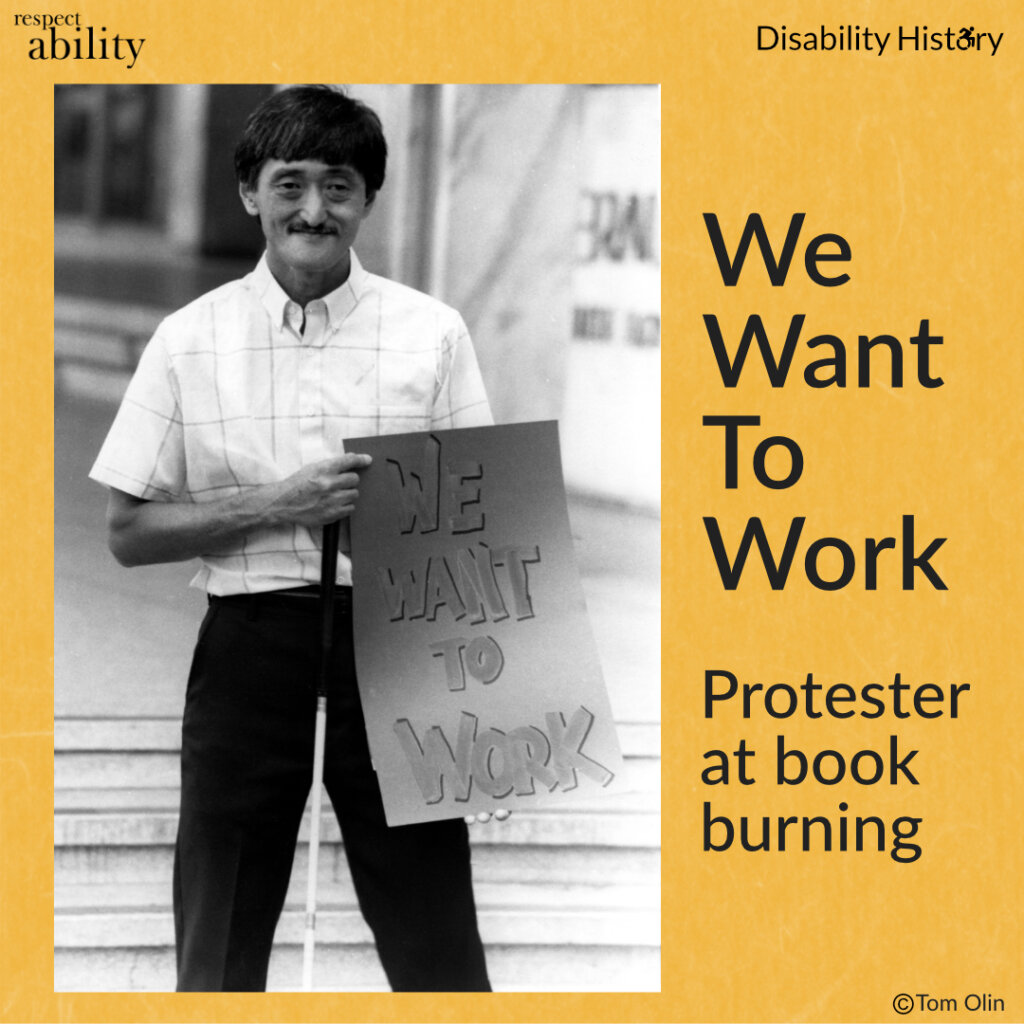

| In protest of these rules that penalized disabled workers, Longmore burned his book in front of the LA Federal Building with a group of disabled protesters chanting “Let Us Work.” |  |

|

As a result, Social Security changed the rules on royalties in what became known as the Longmore Amendment. Many other penalties for working still exist, and activists are fighting to change them to this day. Learn more about Paul Longmore at SFSU’s website. And read an LA Times article from 1988 about Longmore’s protest at their website. |

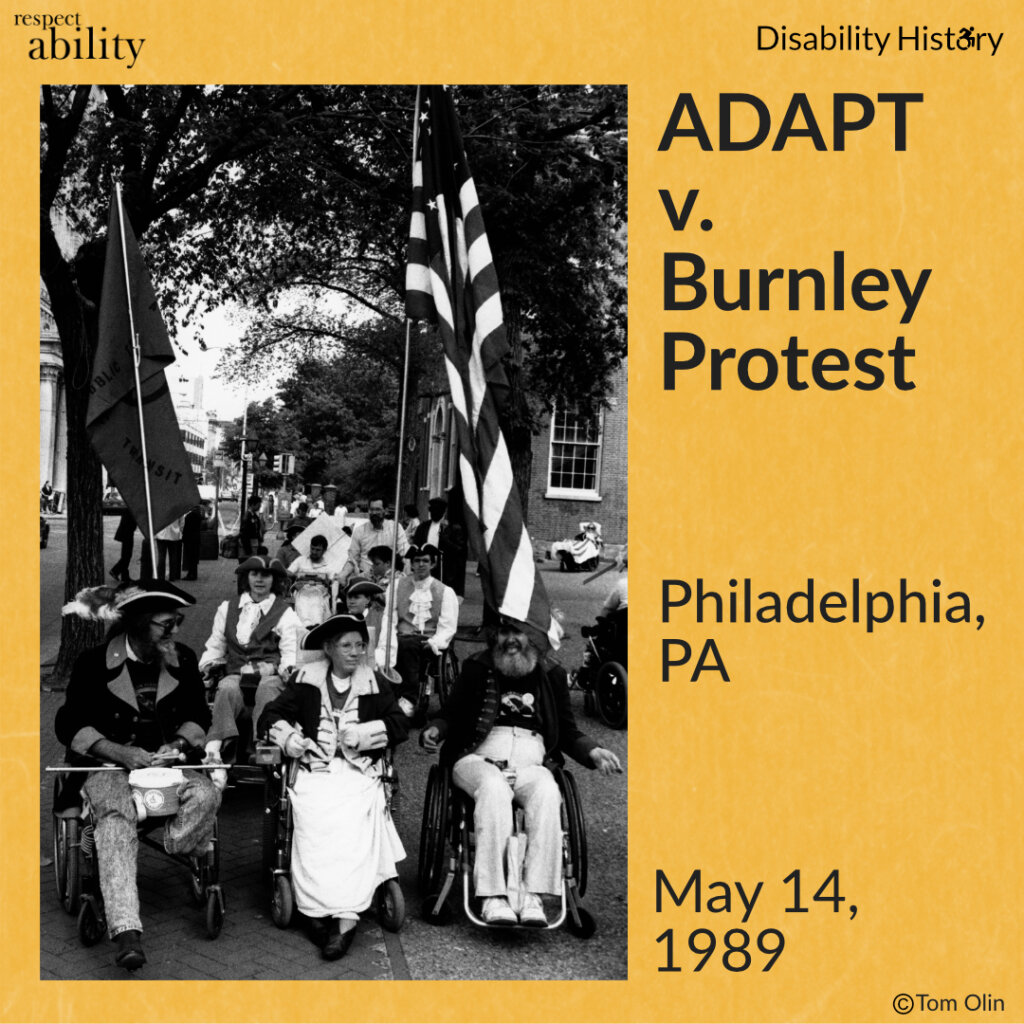

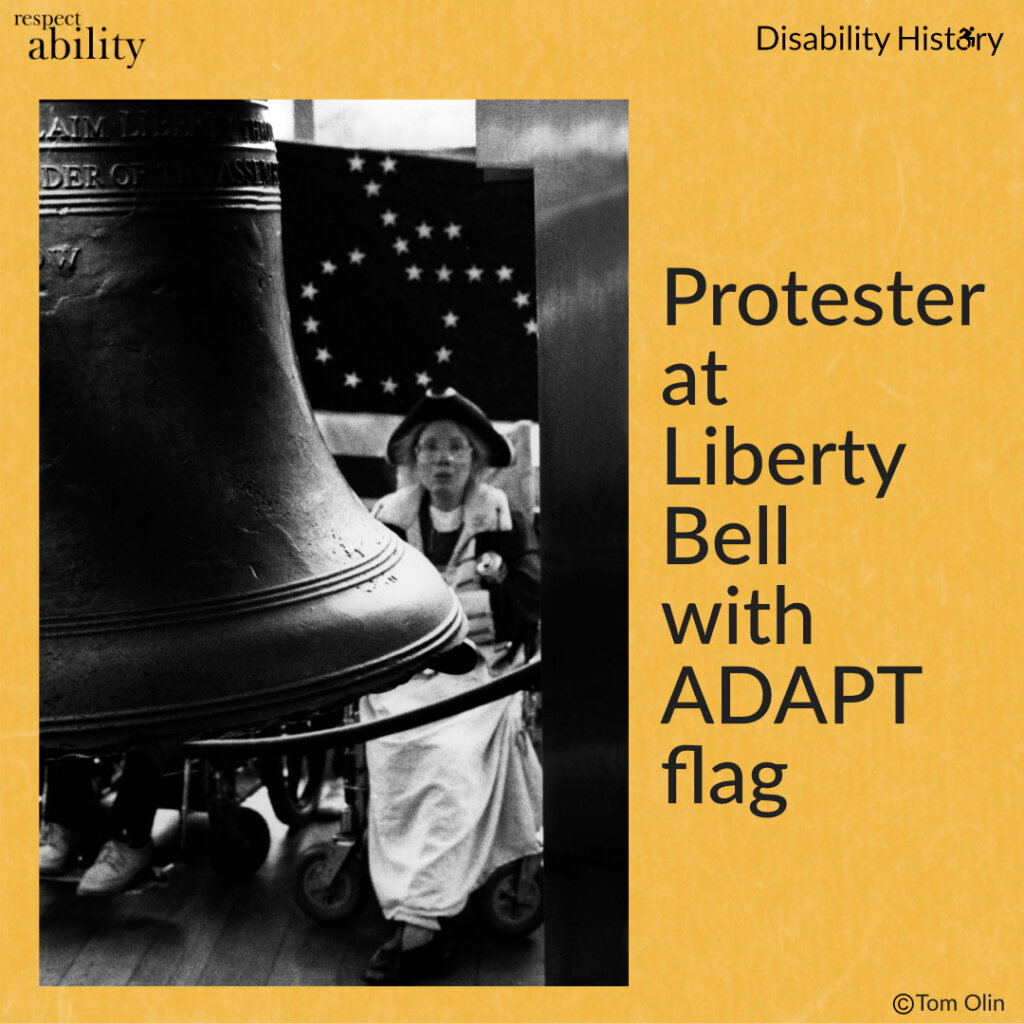

| In the case of ADAPT v. Burnley, the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals in Philadelphia ruled that the 3 percent spending cap on accessible transit in the Department of Transportation budget was too low, and that all newly built buses must have wheelchair lifts. |  |

|

On the eve of this ruling, May 14, 1989, ADAPT activists marched from Independence Hall to the Liberty Bell, surrounding it for hours while wearing revolutionary attire in support of the case. |

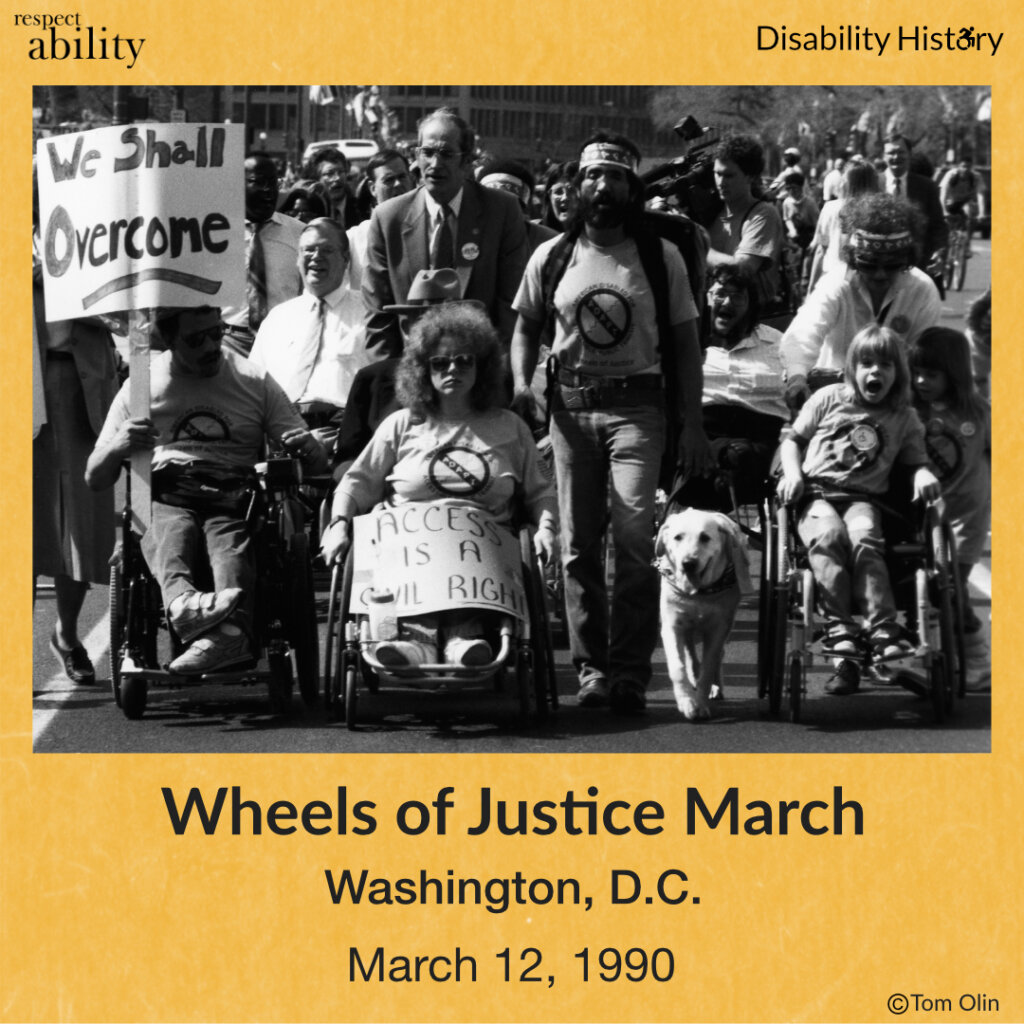

| In the spring of 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act was stalled in Congress, so ADAPT planned a “Wheels of Justice” Campaign in D.C. to push the ADA forward. It began with the Wheels of Justice March from the White House to the Capitol building. 700 people joined the march chanting, “What Do We Want?” “Our ADA!” “When Do We Want It?” “NOW!!” |  |

|

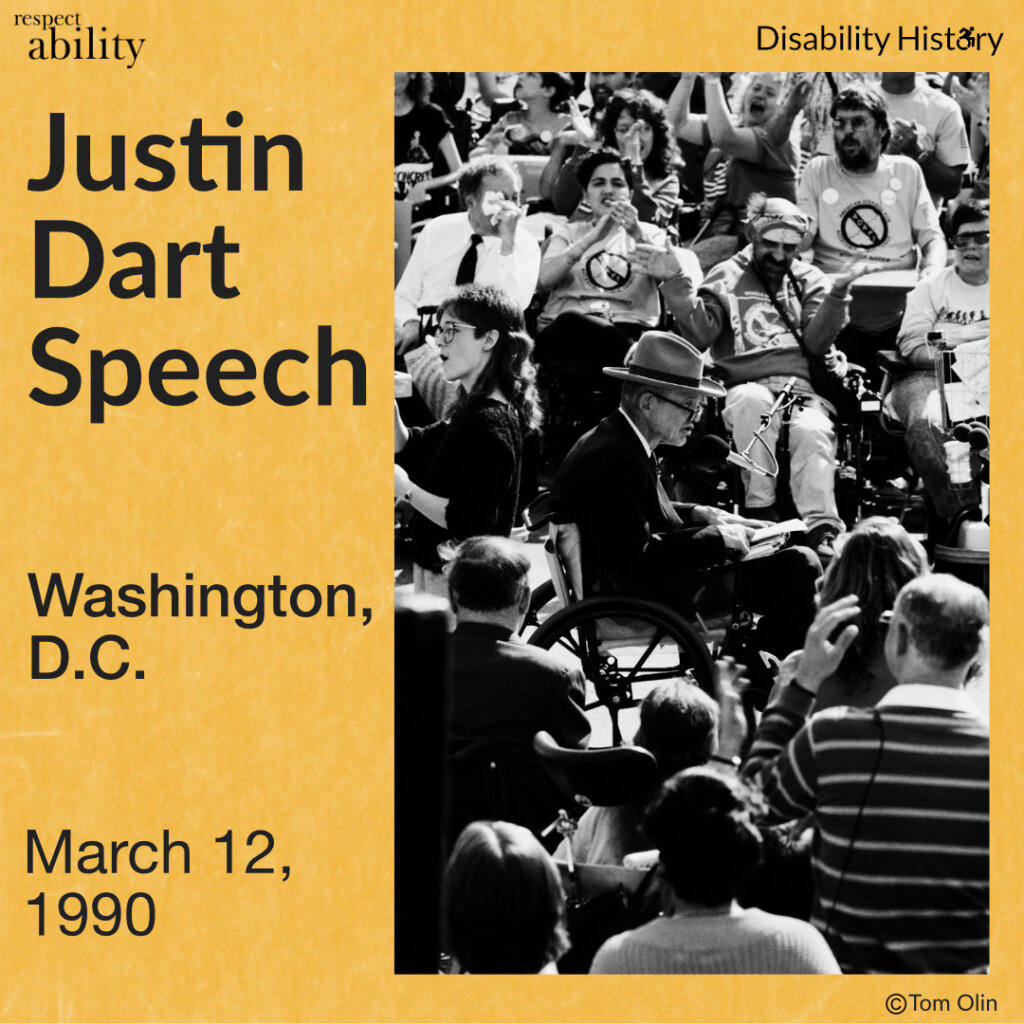

Once at the Capitol, they listened to speeches from ADA advocates including Justin Dart. |

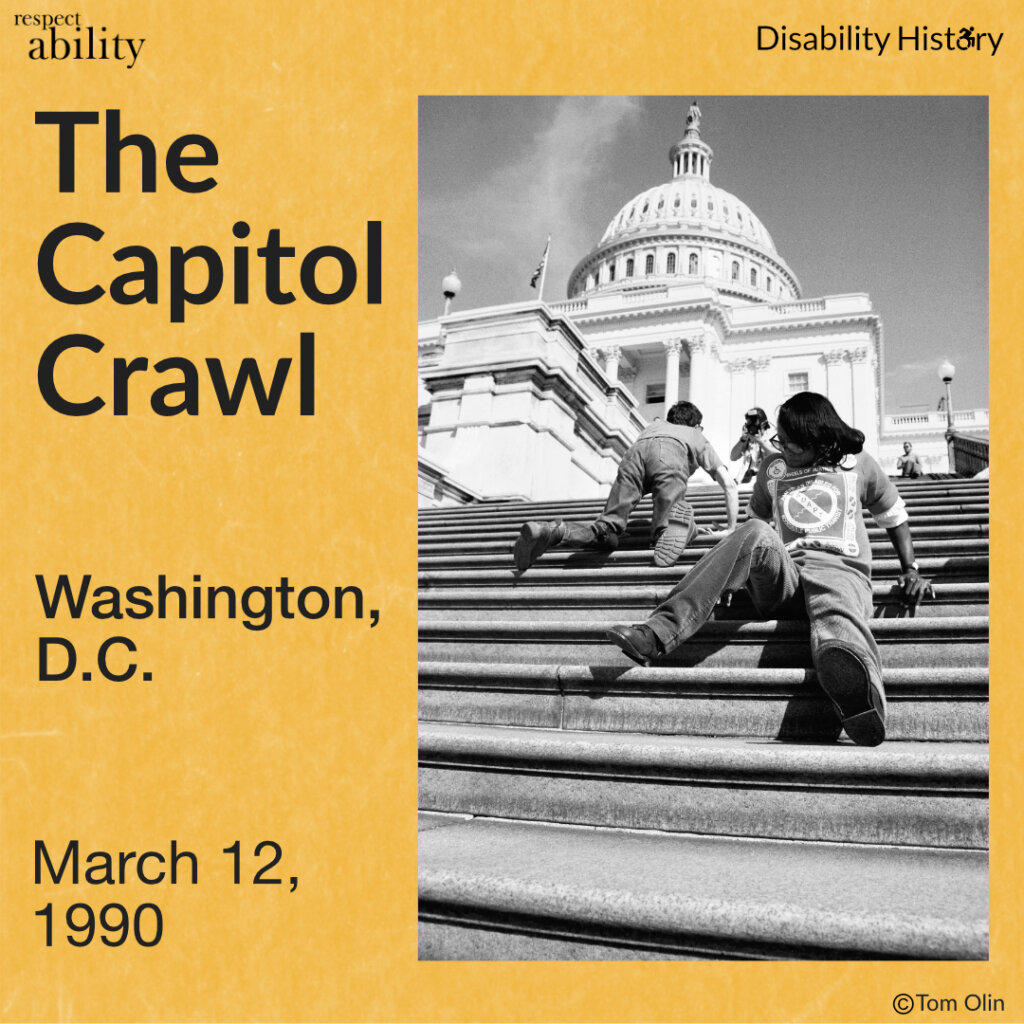

| Then, 60 activists began crawling up the steps, in what is now known as the “Capitol Crawl.” The point of the crawl was to show the indignities and obstacles people with disabilities faced daily because of physical and societal barriers. After reaching the top, activists spoke to House Speaker Tom Foley and House Minority Leader Bob Michels and demanded the ADA be passed without any changes. Learn more about the Capitol Crawl at the History Channel’s website. |  |

|

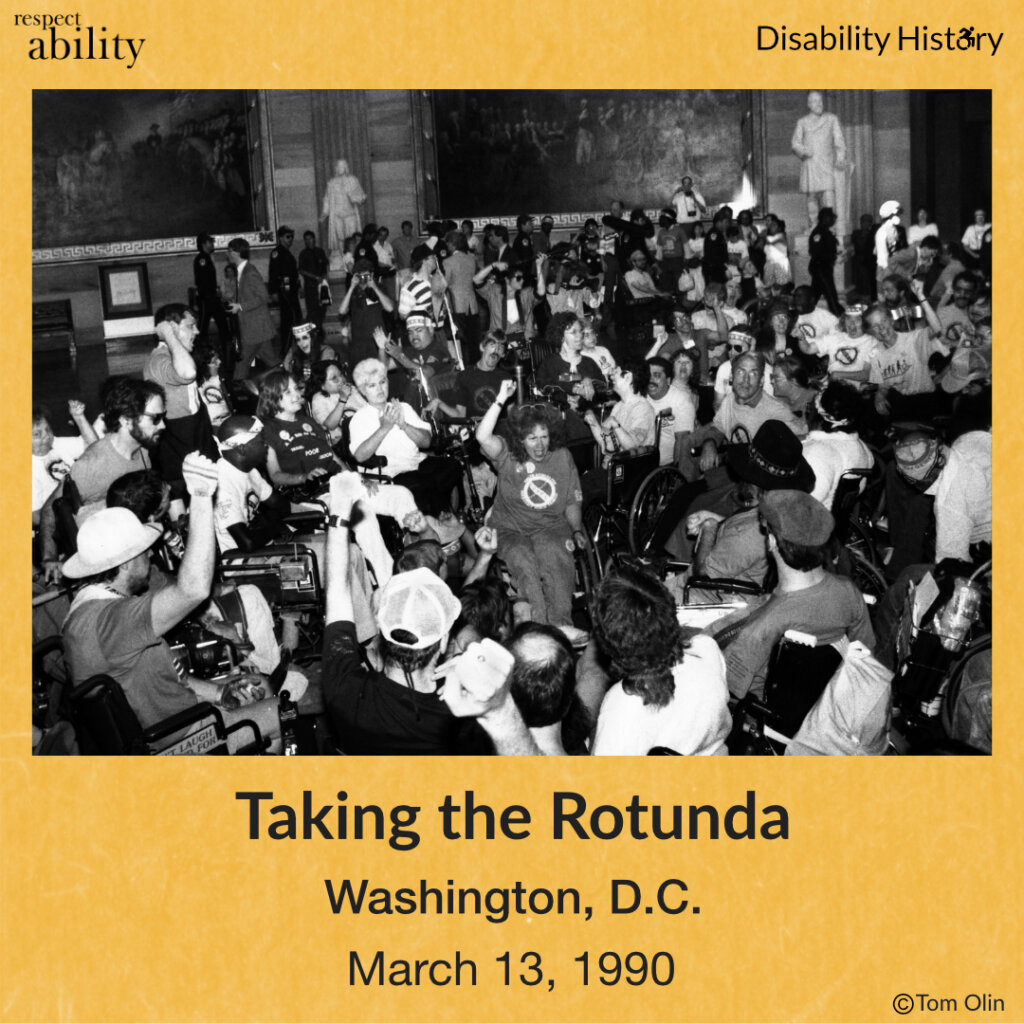

The day after the Capitol Crawl, 200 activists gathered in the Capitol Rotunda and met with House sponsors of the ADA. When they would not guarantee swift passage without changes to the bill, the activists began chanting “ADA now” and refused to leave the rotunda. 104 protesters were arrested by the Capitol Police. |

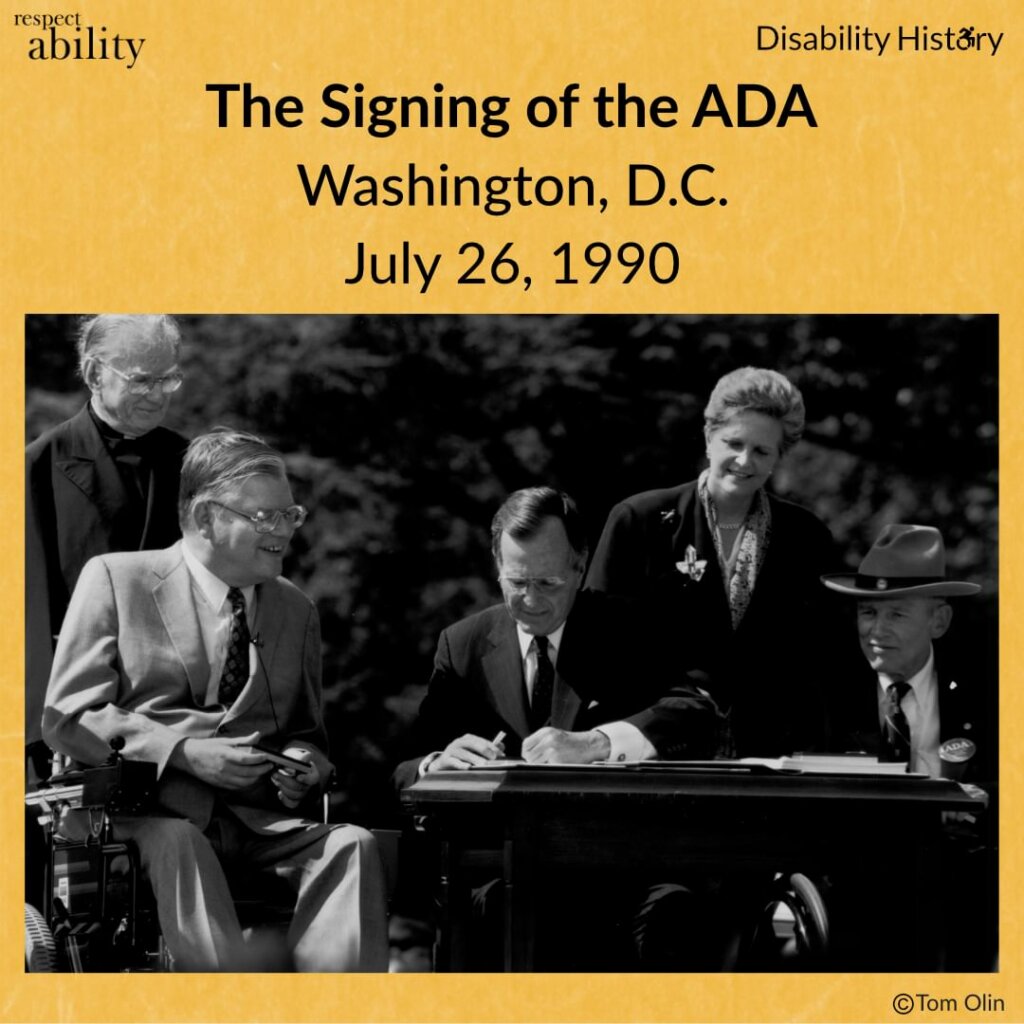

| President George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act into law on July 26, 1990 and said, “Let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down.” Evan Kemp was on his right and Justin Dart on his left. Both were integral in getting the act signed into law, but not without years of activism from other people with disabilities across the United States. Learn more about the ADA at the offiicial website. |  |

|

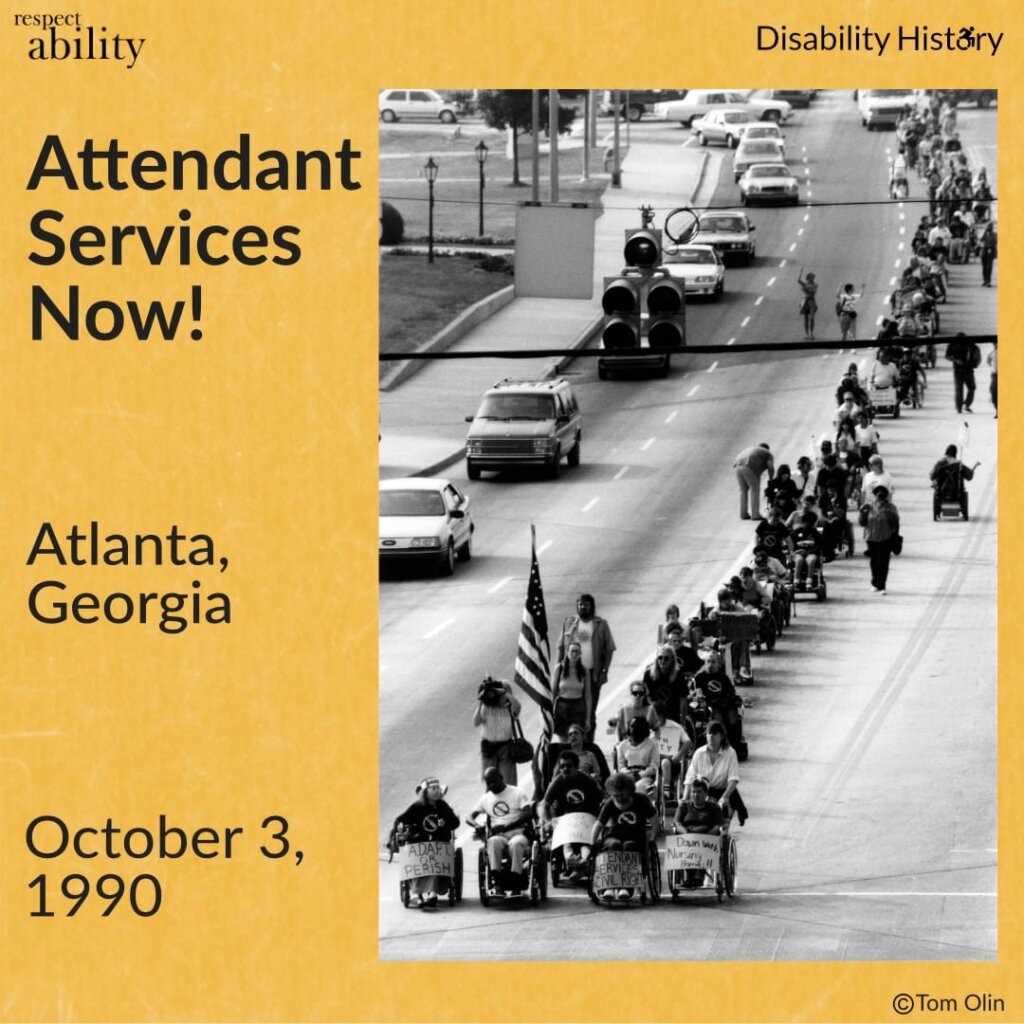

Around two months after the passage of the ADA, ADAPT was in Atlanta starting their new initiative advocating for community based attendant care services. They attempted to get a meeting with the Health and Human Services Secretary, Dr. Louis Sullivan. When that proved unsuccessful, the next day, 200 activists marched down Martin Luther King Drive to the Richard B. Russell Federal Building, blocking the entrances to protest Dr. Sullivan’s interview with NPR. |

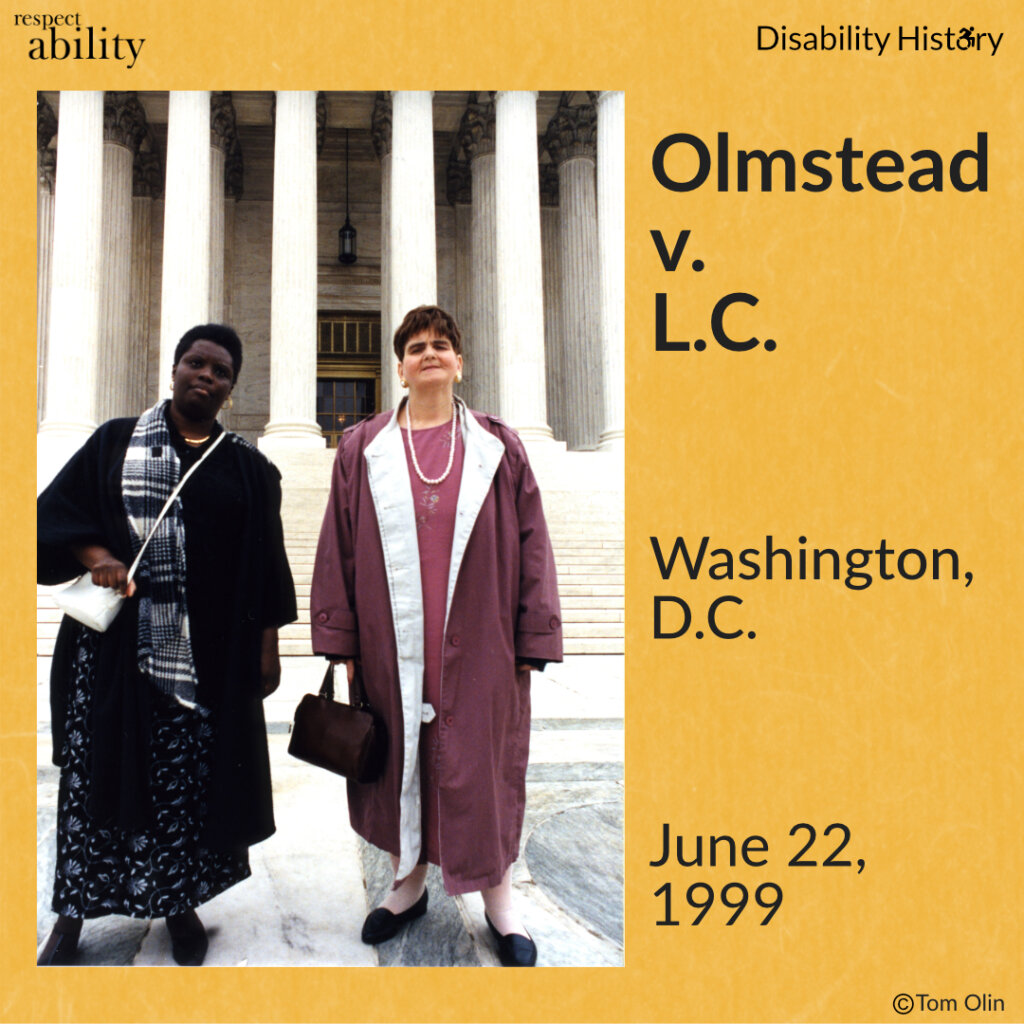

| Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson had intellectual and psychiatric disabilities. After receiving treatment, they wanted to leave a psychiatric hospital and live in their communities with the proper supports. In Olmstead v. L.C. (1990), the Supreme Court ruled that under the ADA, people with disabilities have a right to live and receive services in the community. |  |

|

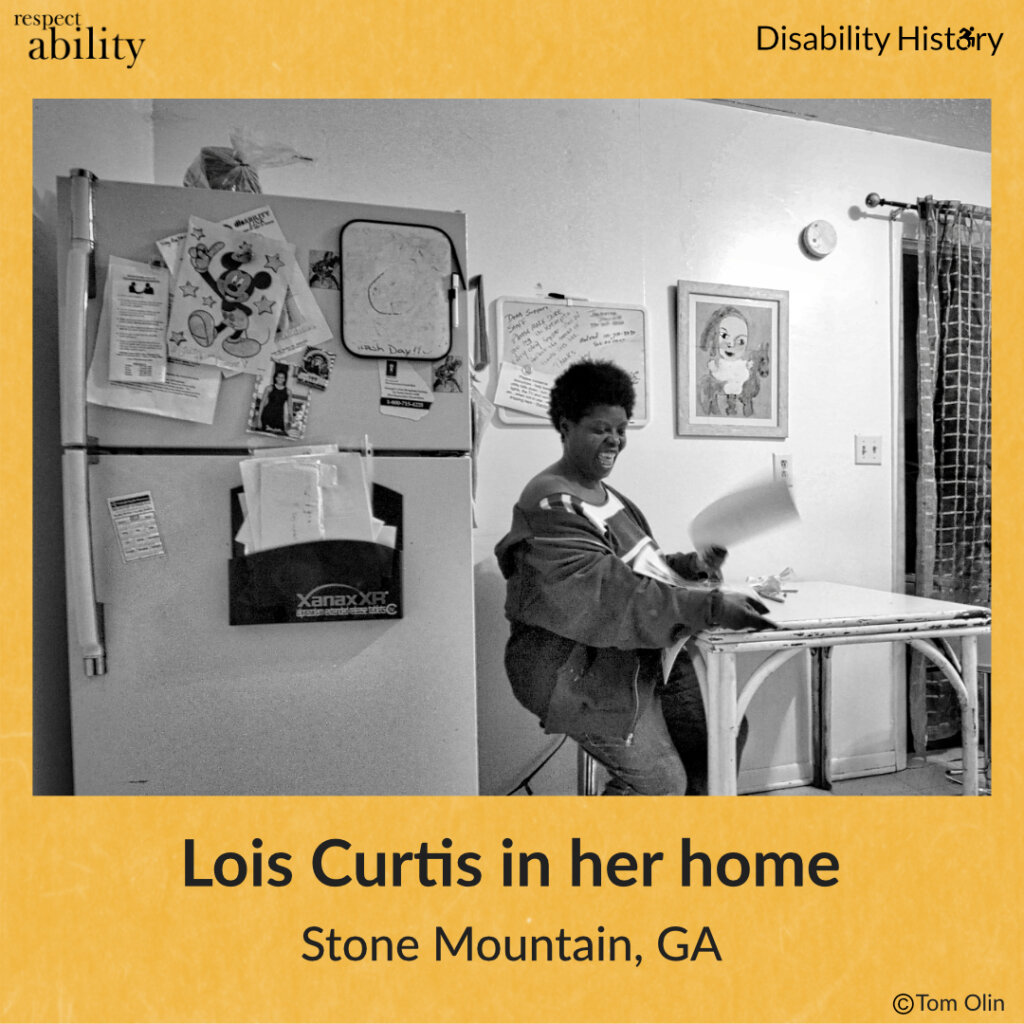

As a result, Curtis and Wilson were able to leave the institution and live in their communities along with many other Americans with disabilities. Lois Curtis passed away from cancer in November 2022. |

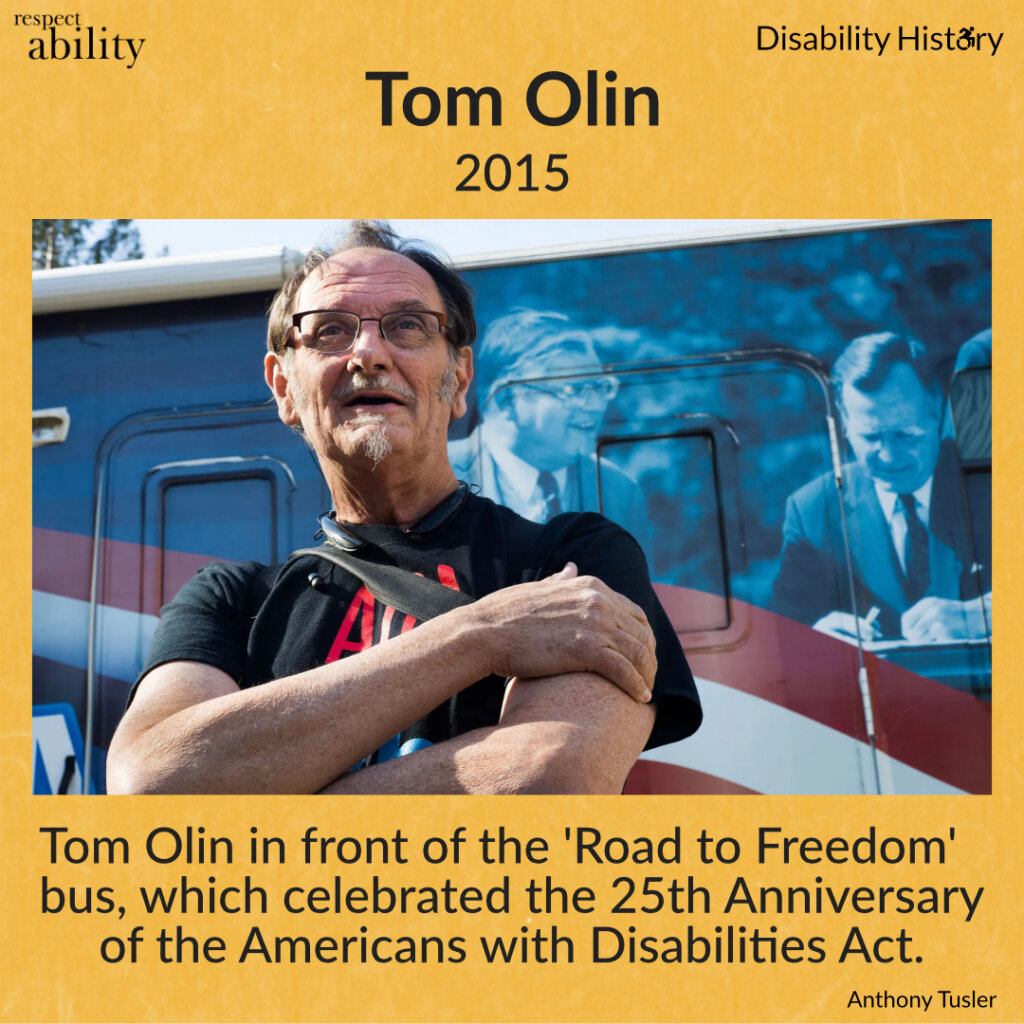

| RespectAbility’s Disability History series would not have been possible without the support of Tom Olin and his collection manager, Dan Wilkins. Tom has been documenting the Disability Rights Movement since 1985. He took photography classes at community college while working as an attendant for people with disabilities in San Fransisco. After photographing the founders of ADAPT at an LA protest, he began photographing key moments in the Disability Rights Movement across the country. Tom continues to participate in the movement and empower the next generation of activists. Learn more about Tom Olin at his collection’s website. |  |